Role and Time Scales of Steel Scrap in Recycling

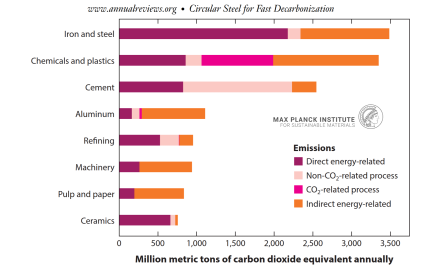

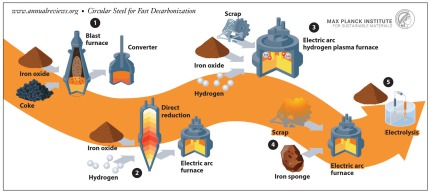

Steel is the most widely recycled metallic material, with a global end-of-life recycling rate exceeding 85 % in many industrialized economies and a scrap recovery rate from production exceeding 95 %. Recycling steel reduces CO₂ emissions by up to 85 % compared to primary production from iron ore via the blast furnace–basic oxygen furnace (BF–BOF) route, primarily due to the elimination of ore reduction and coke production. The principal feedstock for secondary steelmaking in electric arc furnaces (EAF) is steel scrap, which can also partially substitute hot metal in BOF operations.

Scrap flows are generally divided into three categories, each with distinct generation patterns and time delays before re-entering the steel production loop:

- Home scrap (internal scrap): Generated and recycled within the same facility during primary or secondary production, e.g., mill returns, off-cuts, and defective products. Recycling is immediate (< days to weeks), with negligible compositional contamination.

- New scrap (prompt scrap): Arises during downstream manufacturing of steel-containing goods, such as automotive stamping or appliance manufacturing. Collection and recycling typically occur within weeks to months of generation.

- Old scrap (post-consumer scrap): Generated when products reach their end-of-life (EoL) after years to decades of use. This category dominates in volume and is subject to significant time delays, dictated by the product lifetime distribution.

Time Scales and Lifetime Effects of Scrap

The key systemic feature of steel scrap recycling is the inherent time delay between primary production and scrap availability, governed by product lifetimes. According to Raabe et al., average lifetimes are:

- Construction steel: 40–75 years

- Machinery: 20–40 years

- Vehicles: 12–20 years

- Appliances: 5–15 years

- Packaging and short-life goods: < 1 year

These lifetimes create a scrap generation lag that can span decades. For example, a surge in steel production for infrastructure today will generate a scrap “wave” 40–70 years later. This lag is a structural property of the steel cycle and explains why even under maximal recycling rates, primary production cannot be entirely displaced in the short to medium term.

The residence time of steel in use results in a stock-flow dynamic: global in-use steel stocks (in buildings, infrastructure, vehicles, etc.) are estimated at ~30–35 Gt, with annual additions of ~0.5–0.8 Gt. Scrap availability depends on the outflow from this stock, which is determined by the lifetime distribution rather than instantaneous demand for new steel.

Scrap Quality, Contamination, and Downcycling Risks

While home and new scrap are typically clean and directly substitutable for primary steel feedstock, old scrap often contains residual elements (Cu, Sn, Cr, Ni, Mo, etc.) originating from alloyed steels and non-removable impurities from joining, coating, or surface treatments. Copper is particularly problematic: even ~0.1 wt % can cause hot shortness in low-carbon steels due to low Fe–Cu solubility and preferential segregation to grain boundaries during hot working.

The residence time in the use phase also increases the probability of cross-contamination, especially from mixed scrap collection. These effects can necessitate downcycling into lower-specification steels, unless mitigated through improved scrap sorting, dilution with primary steel, or impurity control technologies.

Recycling Yields and System Efficiency

Material flow analyses (World Steel Association, 2022; Graedel et al., 2011) show:

- Global annual scrap use in steelmaking: ~630–700 Mt/year (≈ 35–40 % of total steel production)

- Recycling yield from home and new scrap: > 95 %

- Yield from old scrap: 80–90 %, accounting for collection, sorting, and melt losses

- Collection rates for old scrap: 85–95 % in developed economies, lower in developing regions

The EAF route can use 100 % scrap but is limited by scrap availability and electricity price. The BOF route typically uses 10–30 % scrap, constrained by heat balance and process integration.

Implications for Decarbonization Pathways

The delay inherent in scrap return flows implies that the steel sector cannot rely on recycling alone to achieve near-term decarbonization targets. Even if all currently produced steel were eventually recycled, the time lag before it returns as scrap ensures a persistent need for primary steelmaking for decades.

Raabe et al. stress that reaching a high scrap fraction in the steel mix is a long-term outcome, determined by saturation of in-use stocks in mature economies and the turnover rate of long-lived assets. For rapidly developing regions, in-use stock growth outweighs end-of-life flows, keeping scrap supply structurally insufficient to meet demand.

Key implications:

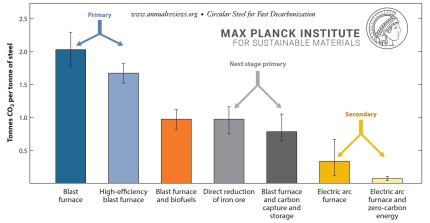

- Short term (0–15 years): Decarbonization must focus on primary production route transformation (e.g., H₂-based DRI, CCUS) alongside maximization of prompt scrap use.

- Medium to long term (15–50 years): Increasing share of scrap-based EAF production as in-use stocks stabilize and old scrap generation rises.

- Ongoing: Need for closed-loop recycling systems, improved scrap sorting, and impurity mitigation technologies to maintain high-quality steel grades from recycled scrap.

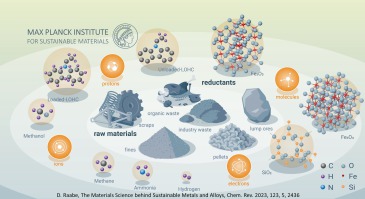

The Materials Science behind Sustainable[...]

PDF-Dokument [5.9 MB]

Summary Points

- Steel’s high recycling rate is offset by the long residence time of steel in use, creating multi-decade delays between production and scrap availability.

- Scrap classification into home, new, and old reflects differences in contamination, yield, and recycling timescale.

- Current scrap flows supply ~35–40 % of steel production; the remainder must come from primary routes until old scrap volumes grow sufficiently.

- Decarbonization strategies must integrate both scrap maximization and low-carbon primary production for at least the next three decades.

- Impurity control is critical for maintaining steel quality in a high-recycling future.

Raabe et al. Circular Steel for Fast Dec[...]

PDF-Dokument [3.3 MB]