Copper in the Global Energy Transition and Electrification

The global energy transition is, at its core, a transition toward electrons. Decarbonization at scale requires the substitution of chemical energy carriers with electrical energy across power generation, transmission, storage, and end-use applications. In this transformation, copper is not merely an enabling material but a structural cornerstone. No other metal combines electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, mechanical ductility, corrosion resistance, and metallurgical processability at the scale and reliability required to electrify modern society. The energy transition is therefore inseparable from the physical metallurgy, availability, and sustainable use of copper.

At the most fundamental level, electrification demands efficient charge transport. Copper’s room-temperature electrical conductivity of approximately 5.96 × 10⁷ S·m⁻¹, exceeded only marginally by silver, makes it the material of choice wherever electrical losses must be minimized. In power systems, even fractional increases in resistive losses translate directly into higher generation demand, increased infrastructure requirements, and higher system-level emissions. The choice of copper over alternative conductors is therefore not merely economic but thermodynamic: lower resistivity reduces Joule heating, improves energy efficiency, and enhances system reliability across the entire value chain of electricity generation and use.

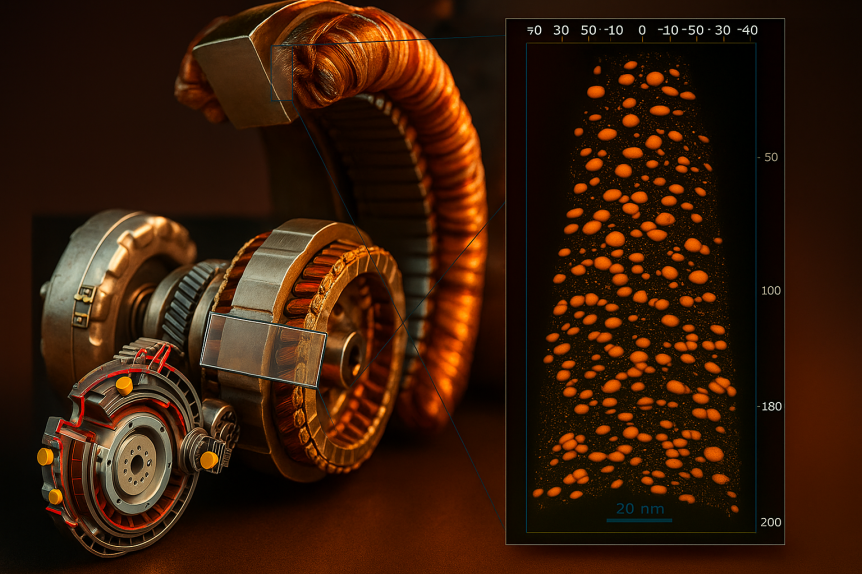

Rapid annealing (4–10 s) induced primary crystallization of soft magnetic Fe–Si nanocrystals in a Fe73.5Si15.5Cu1Nb3B7 amorphous

alloy has been systematically studied by atom probe tomography in comparison with conventional annealing (30–60 min). It was found

that the nanostructure obtained after rapid annealing is basically the same, irrespective of the different time scales of annealing. This

underlines the crucial role of Cu during structure formation. Accordingly, the clustering of Cu atoms starts at least 50 C below the onset

temperature of primary crystallization. As a consequence, coarsening of Cu atomic clusters also starts prior to crystallization, resulting in

a reduction of available nucleation sites during Fe–Si nanocrystallization. Furthermore, the experimental

Atom probe tomography ultrahigh nanocrys[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.6 MB]

The expansion of renewable electricity generation magnifies role the Copper. Wind turbines, photovoltaic systems, and hydroelectric generators are all copper-intensive technologies. In wind turbines, copper is essential in generator windings, power cables, transformers, and grounding systems. Modern multi-megawatt offshore wind turbines can contain several tonnes of copper per unit, reflecting both the scale of electrical power handled and the requirement for long-term reliability under cyclic mechanical and environmental loading. In photovoltaic systems, copper is used extensively in inverters, transformers, cabling, and increasingly in cell and module interconnections as power densities rise. Unlike fossil-based generation, renewable systems are more distributed and materials-intensive per unit of delivered energy, amplifying the structural demand for copper.

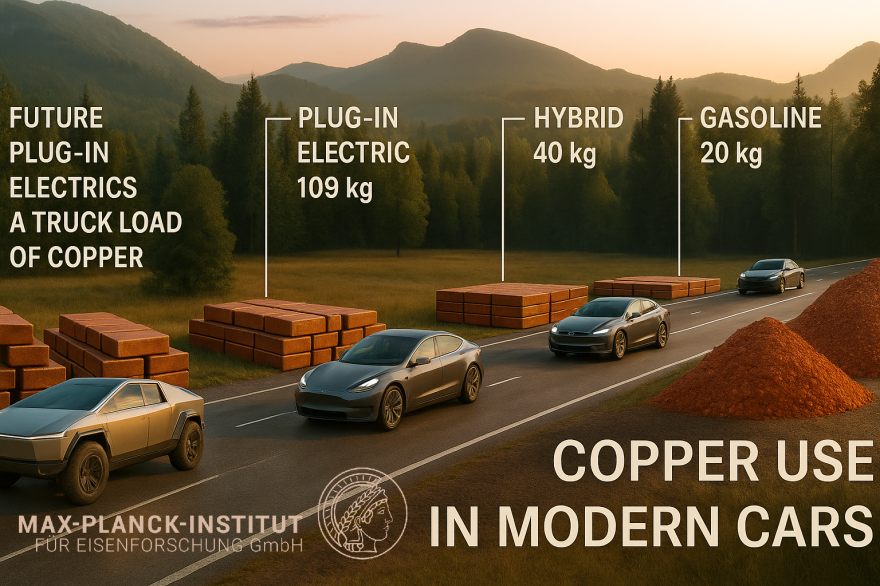

Electrification of end-use sectors further accelerates this trend. Electric vehicles represent one of the most copper-intensive consumer technologies ever deployed at scale. A battery electric vehicle typically contains two to four times more copper than an internal combustion engine vehicle, with copper required in traction motors, power electronics, battery connections, high-voltage cabling, charging interfaces, and auxiliary systems. Beyond the vehicle itself, charging infrastructure adds an additional layer of copper demand through grid upgrades, transformers, and high-power charging stations. From a systems perspective, each unit of electrified mobility embeds copper not only in the product but also in the supporting electrical ecosystem.

The physical metallurgy of copper is central to why it fulfills these roles so effectively. Copper’s face-centered cubic crystal structure provides exceptional ductility, enabling the production of wires, foils, and complex conductor geometries without fracture. This ductility is retained across a wide temperature range, allowing copper conductors to tolerate thermal cycling, vibration, and mechanical deformation during installation and service. At the same time, copper exhibits sufficient mechanical strength, particularly when work-hardened or microalloyed, to maintain dimensional stability in demanding applications such as high-speed motors and high-current busbars.

Thermal conductivity is an equally critical attribute in electrified systems. As power densities increase, thermal management becomes a limiting factor in motors, inverters, transformers, and battery systems. Copper’s thermal conductivity, on the order of 400 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ at room temperature, enables efficient heat dissipation, reducing the need for oversized cooling systems and improving component lifetime. In power electronics, where thermal gradients directly affect efficiency and reliability, copper functions simultaneously as an electrical conductor and a thermal pathway, integrating multiple functional requirements into a single material solution.

From a reliability standpoint, copper’s corrosion resistance and chemical stability are decisive. Electrical infrastructure is expected to operate for decades under variable environmental conditions. Copper forms stable surface films that protect against further degradation in many atmospheres, reducing maintenance requirements and failure rates. This durability is particularly important for renewable energy installations and grid components deployed in remote or offshore environments, where access for repair is limited and costly. The long service life of copper-containing components lowers the material intensity and environmental footprint of the energy transition when evaluated over full life cycles.

The scale of the energy transition introduces a quantitative dimension that underscores copper’s essentiality. Electrification pathways consistent with climate stabilization scenarios imply a substantial increase in global electricity generation, transmission capacity, and storage. Each of these expansions is copper-intensive. Transmission and distribution networks require copper in conductors, transformers, switchgear, and substations. As grids become more interconnected and resilient, conductor lengths increase, redundancy grows, and power electronics proliferate, all reinforcing copper demand. Unlike many specialty materials, copper demand in the energy transition is not limited to niche technologies but spans the entire infrastructure backbone.

This raises a critical metallurgical and societal challenge: copper must be available in sufficient quantity and quality to support the transition without creating new resource constraints. Copper is geologically finite, geographically concentrated, and increasingly complex to extract. Ore grades have declined steadily over the past decades, increasing energy consumption and environmental impact per unit of primary copper produced. From a physical metallurgy perspective, this reality shifts attention toward secondary copper, recycling, and impurity tolerance as strategic priorities.

Copper is inherently well suited to recycling. Its crystal structure, thermodynamic stability, and high melting point allow repeated remelting without fundamental degradation of intrinsic properties. In principle, copper can be recycled indefinitely. In practice, however, the challenge lies in impurity accumulation. Elements such as iron, nickel, zinc, tin, and lead enter copper streams through mixed scrap and complex products. Even at low concentrations, these impurities can degrade electrical conductivity through electron scattering, undermining copper’s functional value for energy applications. The energy transition therefore places unprecedented demands on the control of copper purity and on the development of metallurgical routes that balance conductivity requirements with realistic scrap compositions.

This tension highlights the importance of physical metallurgy in shaping sustainable copper systems. Understanding how specific impurities interact electronically and structurally with the copper lattice allows informed decisions about acceptable impurity levels for different applications. Not all copper in the energy transition must meet the highest conductivity standards. Structural conductors, grounding systems, and thermal components may tolerate higher impurity contents than high-voltage windings or microelectronic interconnects. Differentiated quality strategies, grounded in metallurgical science, are essential to maximizing the utility of recycled copper without excessive refining energy.

Copper’s role in the energy transition is therefore not static but evolving. It is simultaneously a conductor, a thermal manager, a structural material, and a recyclable resource. Its physical metallurgy connects atomic-scale electronic structure to planetary-scale energy flows. Few materials occupy such a central position at the intersection of physics, engineering, and sustainability. The success of global electrification will depend not only on deploying more copper, but on deploying it intelligently—designed, processed, recycled, and allocated according to deep understanding of its metallurgical behavior.

In this sense, copper is not merely a beneficiary of the energy transition; it is one of its limiting reagents. Ensuring that copper continues to perform its essential functions under conditions of unprecedented demand is a grand challenge for materials science. Addressing it requires advances in extraction, alloy design, recycling technology, and system-level integration, all rooted in the physical metallurgy of this deceptively simple metal. The energy transition will be electrified, or it will not happen at all—and if it is electrified, it will be built, quite literally, on copper.