Hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron oxide: heterogeneity at pellet- and microstructure-scales

Global Steel Demand and Carbon Emissions: An Overview

The steel industry stands at a critical crossroads, balancing the essential role of steel in modern infrastructure with the urgent need for decarbonization. This relationship is defined by two primary factors: rising global consumption and the chemical nature of traditional production.

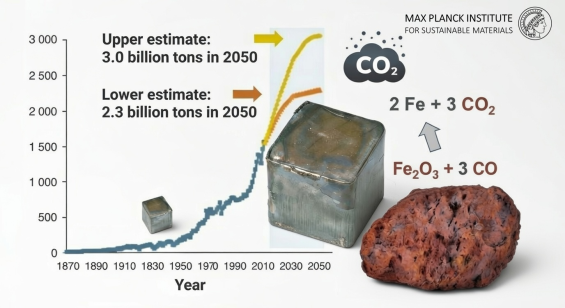

The Carbon-Fueled Redox Reaction

The primary challenge in reducing the industry's environmental footprint lies in the carbon-fueled redox (reduction-oxidation) reaction used in traditional Blast Furnace-Basic Oxygen Furnace (BF-BOF) pathways.

In this process, coke (carbon) acts as both a fuel and a reducing agent to strip oxygen from iron ore. The simplified chemical reaction is:

-

The Emission Driver: Because carbon is chemically required to reduce iron ore into liquid iron in these furnaces, CO2 is an inherent byproduct of the reaction rather than just a result of energy consumption.

-

Industrial Impact: This specific chemical dependency is the reason the steel industry currently accounts for approximately 7% to 9% of global anthropogenic emissions.

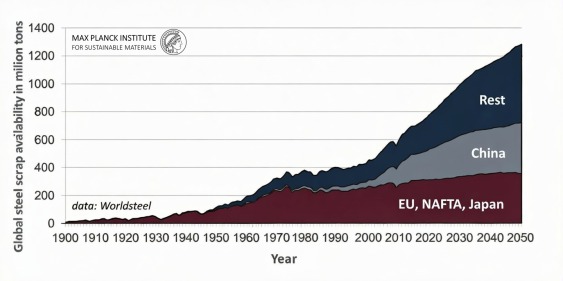

Evolution of Global Steel Demand

Based on data from the World Steel Association and validated forecast models, global demand for steel has shown consistent growth, driven largely by rapid urbanization and industrialization in emerging economies.

-

Historical Trends: Over the past two decades, production capacity has scaled significantly to meet the needs of the construction, automotive, and energy sectors.

-

Future Projections: Forecast models suggest that while demand in mature markets may plateau, the global total will continue to rise as developing nations invest in sustainable infrastructure and renewable energy technologies (which are surprisingly steel-intensive).

The Challenge of Sustainable Steel Production

Because steel is exceptionally durable—found in long-lasting buildings, machinery, and vehicles—there is currently insufficient scrap available to meet global market demands. Over 75% of all steel ever produced remains in use. Consequently, only about one-third of total global production can be sourced from recycled scrap, even though the industry aims to increase this fraction.

A significant hurdle in recycling is the gradual accumulation of "tramp elements," such as copper. These contaminants enter the supply chain through improperly sorted post-consumer scrap and the rising use of copper in modern vehicles. Because of these constraints, primary iron synthesis from ore reduction will remain necessary alongside recycling for several decades.

Environmental Impact of Primary Production

Currently, more than 70% of global raw iron is produced in blast furnaces using carbon monoxide as the primary reducing agent. This process consumes approximately 2.6 billion tons of iron ore annually to produce 1.28 billion tons of pig iron (the iron-carbon alloy tapped from the furnace).

The environmental cost of this method is significant:

-

Carbon Footprint: Every ton of steel produced via the blast furnace and basic oxygen furnace route generates approximately 1.9 tons of CO2.

-

Global Emissions: Iron and steelmaking are the largest single industrial sources of greenhouse gases, accounting for 7–8% of all global CO2 emissions.

-

Sector Impact: This represents 35% of all CO2 generated within the manufacturing sector.

Projections suggest these emissions will continue to increase significantly through 2030 unless the industry implements sustainable, disruptive technological changes.

Hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron [...]

PDF-Dokument [3.8 MB]

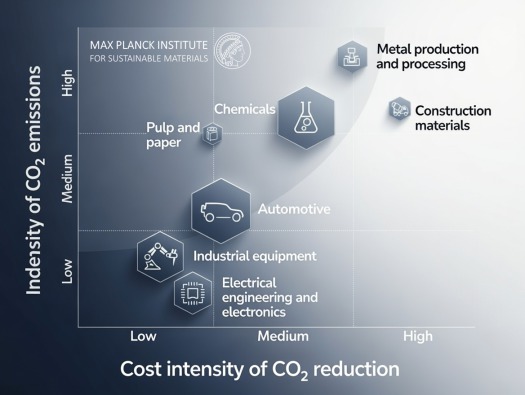

As exlained above steel manufacturing accounts for approximately 35% of all global industrial CO2 emissions, primarily driven by the reliance on carbonaceous reductants for iron ore processing.

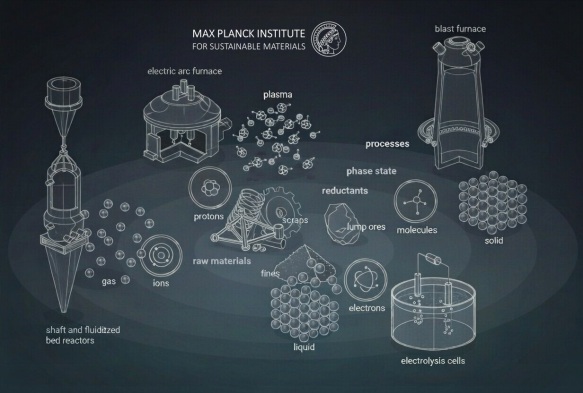

Consequently, the transition toward sustainably produced hydrogen is a critical focus of contemporary metallurgical research. Hydrogen-based Direct Reduction (HyDR) represents a promising pathway, leveraging the industry's existing infrastructure for Direct Reduction (DR) shaft furnaces, which traditionally utilize CH4 or CO.

While hydrogen exhibits significantly higher diffusivity through iron oxide pellet agglomerates compared to carbon-based reductant counterparts (e.g. CO), the net reduction kinetics of HyDR remain insufficient for large-scale industrial-scale throughput. Furthermore, hydrogen consumption in DRI practice far exceeds the theoretical stoichiometric minimum requirements.

We investigate the fundamental mechanisms governing reduction efficiency and metallization by examining the role of spatial gradients, morphology, and internal microstructures within ore pellets. Utilizing a multi-modal analytical approach—comprising synchrotron high-energy X-ray diffraction (HEXRD), electron microscopy, and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD)—we characterize the complex interplay between phase transformations, internal interfaces, and nucleation mechanisms. These insights provide a scientific framework for the design of tailored ore pellets optimized for accelerated and highly efficient HyDR.

The current annual consumption of iron ores for this process amounts to 2.3 billion tons, producing approximately 1.32 billion tons of pig iron, the historical name for the near-eutectic iron-carbon alloy tapped from blast furnaces. Each ton of steel produced through blast furnaces and the subsequent basic oxygen furnace route generates about 1.9 tons of carbon dioxide. These figures establish iron and steelmaking as the most substantial single sources of greenhouse gas globally, accounting for 7–8% of total carbon dioxide emissions and approximately 35% of all carbon dioxide produced in the manufacturing sector. Growth rate projections suggest a further massive increase in these emissions through at least 2030 if no sustainable and disruptive technology changes are implemented.

The fundamental challenge lies in decarbonizing iron and steel production while maintaining economic viability. Currently, carbon-based substances serve as reductants for iron ores, making them critical contributors to global warming. Alternative reduction methods with potentially net-zero emissions for extracting iron from its ores must be urgently studied, identified, matured, and implemented based on thorough understanding of the underlying physical and chemical mechanisms.

Several strategies are conceivable, including a variety of solid, molecular, ionic, proton, and electron-based reductants. The associated synthesis and reduction methods can be combined in various ways. A particularly promising alternative approach for large-scale and sustainable iron oxide reduction is the use of hydrogen gas and its carriers, provided that reducing agents originate from sustainable or low-carbon sources.

Hydrogen-Based Direct Reduction Fundamentals

Hydrogen-based direct reduction (HyDR) with molecular hydrogen represents an attractive processing technology, given that direct reduction furnaces are routinely operated in the steel industry but with methane or carbon monoxide as reductants. The key advantage of hydrogen is that it diffuses considerably faster through shaft-furnace pellet agglomerates than carbon-based reductants.

The HyDR process involves multiple phase transformations. At temperatures above 570°C, HyDR proceeds along the sequence: hematite (Fe2O3) to magnetite (Fe3O4) to wüstite (Fe(1−x)O) to alpha-iron (α-Fe) or gamma-iron (γ-Fe). At temperatures below 570°C, wüstite is no longer thermodynamically stable, and the reduction reaction proceeds in the order hematite to magnetite to alpha-iron. The overall reaction is endothermic when using hydrogen as the reductant.

Despite its theoretical advantages, the net reduction kinetics in HyDR remains extremely sluggish for high-quantity steel production, and hydrogen consumption substantially exceeds the stoichiometrically required amount. This inefficiency presents a significant barrier to industrial implementation. Understanding the mechanisms controlling reduction kinetics at multiple length scales—from the global pellet scale to the microstructural scale—is essential for developing more efficient processes.

Research Objectives

Previous investigations have focused primarily on global reduction thermodynamics, kinetics, and the effects of process parameters such as gas flow rate, temperature, and pressure, rather than on microscopic nucleation and growth mechanisms or gradients through feedstock dimensions. The literature has identified that reaction rates are often controlled by nucleation and growth of phases, as well as phase boundary reactions. Some models have attempted to account for the role of pellet granularity in reduction kinetics.

The present investigation aimed to gain further insights into how pellet morphology and internal microstructure influence overall reduction efficiency and metallization. Understanding the interplay of different phases with internal interfaces, free surfaces, and associated nucleation and growth mechanisms provides a basis for developing tailored ore pellets that are highly suited for fast and efficient HyDR.

Experimental Methods

Materials and Setup

Commercial direct reduction hematite pellets with a diameter of approximately 11 millimeters were investigated. The pellets had a chemical composition of 0.36 weight percent iron oxide (FeO), 1.06 weight percent silica (SiO2), 0.40 weight percent aluminum oxide (Al2O3), 0.73 weight percent calcium oxide (CaO), 0.57 weight percent magnesium oxide (MgO), 0.19 weight percent titanium oxide (TiO2), 0.23 weight percent vanadium, 0.10 weight percent manganese, with hematite (Fe2O3) comprising the balance. The pellets also contained traces of phosphorus, sulfur, sodium, potassium, vanadium, and titanium.

The pellets were isothermally exposed to pure hydrogen with a constant flow rate of 0.5 liters per minute at 700°C in a thermogravimetric configuration. Mass loss was continuously monitored during reduction experiments. The reduction degree was determined from experimental mass loss divided by theoretical mass loss, with complete reduction of hematite to iron as the reference.

Characterization Techniques

Phase distribution along the pellet radius was characterized using synchrotron high-energy X-ray diffraction (HEXRD). A disk sample approximately 2 millimeters thick was sliced from the center of the spherical pellet using a diamond wire saw. Measurements were conducted in transmission mode at a fixed beam energy of approximately 100 kiloelectron volts, with a corresponding wavelength of 0.0124 nanometers. The probing beam size was 0.5 millimeters by 0.5 millimeters. Debye-Scherrer diffraction rings were recorded by an area detector and integrated using specialized software. Phase fractions were calculated based on Rietveld refinement methods.

Local microstructure was further analyzed using secondary electron imaging, electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), and correlated energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) in scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The step size for EBSD measurement was 50 nanometers. Acquired EBSD and EDX data were analyzed using specialized software packages.

Results

Overall Reduction Kinetics

The experimentally observed reduction kinetics in terms of reduction degree for hydrogen-based direct reduction of commercial hematite pellets revealed distinct rates across different reduction stages. The reduction rates of the first two reduction steps—from hematite to magnetite and from magnetite to wüstite—were high at approximately 0.5 to 1.8 × 10^-3 per second.

The wüstite reduction to alpha-iron started considerably slower, at approximately 0.6 × 10^-3 per second, and continuously slowed toward the end of the redox reaction. The reduction degree reached 95% after approximately 37 minutes and 98% after 52 minutes, indicating that reduction in this final stage was extremely sluggish and complete metallization was not fully obtained.

The most common feature across all sequential phase transformation steps was the gradual deceleration of transformation rate during transformation within the same phase regime. An important reason for this deceleration was discovered in the pellet microstructure. During the early stages of individual phase transformations, the material showed a very rich density of lattice defects, particularly high porosity from gradual mass loss, delamination at hetero-interfaces, and cracking from high-volume mismatch between adjacent phases and resulting mechanical stresses.

A critical aspect was that pellets contained a high-volume fraction of inherited pores. This feature facilitated rapid outbound mass transport of oxygen and removal of water from surface reaction fronts, always enabling rapid nucleation and growth near internal free surfaces at the beginning of reduction. However, as the reaction progressed, remaining oxide regions became increasingly surrounded by reduction products. As the remaining volume became smaller and highly dispersed, considerably fewer lattice defects were directly connected as pathways for rapid diffusion. Toward the end of reduction steps, small remaining oxide regions were less frequently in contact with delamination and cracking features, and the remaining oxide regions were surrounded by denser reaction products that impeded oxygen removal.

Through-Pellet Heterogeneity of Microstructures

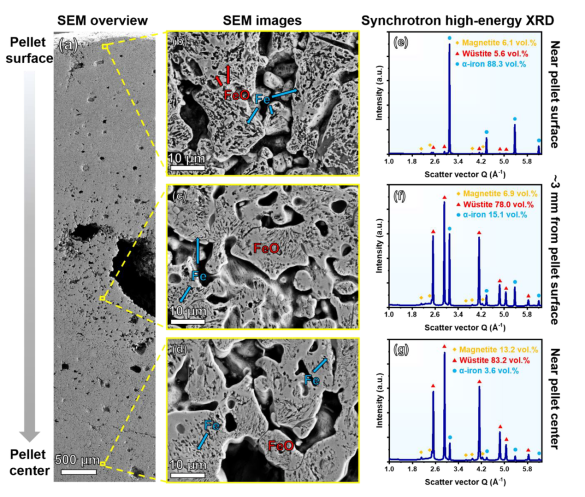

Examination along the radius of a hematite pellet reduced with hydrogen at 700°C for 30 minutes revealed a distinct gradient in microstructure, porosity, and phases between near-surface and interior regions.

The pellets are granular agglomerates consisting of sintered polycrystalline substructure units that are hierarchically stacked together with large pore regions among them. These large pores exist both between sintered substructure units and within the material structure.

In near-surface regions of pellets, oxygen can rapidly diffuse outbound either toward the outer free pellet surface or into adjacent free volume in the form of inherited pores. On these free surfaces, oxygen combines with hydrogen to form water. Hydrogen intrudes from outer free pellet surfaces, making the outer regions naturally the ones reduced most rapidly. This basic kinetic scenario is supported quantitatively by microstructure gradients measured through X-ray diffraction analysis.

The pellet surface revealed the highest metallization degree of 88.3 volume percent alpha-iron, with remaining small fractions consisting of wüstite (5.6 volume percent) and magnetite (6.1 volume percent). In contrast, metallization dropped dramatically to 15.1 volume percent alpha-iron in the region approximately 3 millimeters below the pellet surface, with large portions remaining as iron oxides: 78.0 volume percent wüstite and 6.9 volume percent magnetite. No significant difference was observed in phase fractions in the center region of the pellet (83.2 volume percent wüstite, 13.2 volume percent magnetite, and 3.6 volume percent alpha-iron) compared with the region approximately 3 millimeters below the surface. This result indicated a very drastic difference in reduction rate between near-surface regions and pellet interiors.

Local Microstructure Features

Examination of microstructure and phase topology in regions approximately 2 millimeters below the surface—within the topochemical interface of the wüstite-to-iron transition—revealed fundamental characteristics of the entire HyDR process. Reduced iron appeared bright in backscattered electron images, whereas wüstite appeared in darker gray contrast. Black regions represented pores inherited from pellet sintering and those formed through mass loss during reduction.

An important feature was that all formed iron was located adjacent to free surfaces. This feature matched kinetic expectations regarding fast hydrogen intrusion through gaseous surface diffusion along free volume regions and fast oxygen removal rates at internal interfaces, where water formed and accumulated. At reduction beginning, hydrogen ingress, oxygen removal, and hydrogen-oxygen recombination to water occurred only in large percolating pore regions inherited from pelletizing. However, several pores evolved during gradual oxygen removal. This phenomenon appeared as evolving nanoscale porosity inside the wüstite region. With ongoing gradual oxygen removal, these pores further grew and locally recombined into larger ones over the reduction course.

The nucleation barrier for iron formation is likely smaller on free surfaces than in the interior. This occurs because heterogeneous nucleation provides a nucleation advantage, where a portion of required interface energy is already provided by inner open surfaces. Additionally, elastic stress relaxation occurs upon iron nucleation on the surface. Given the large volume difference between iron and wüstite—exceeding 40%—this aspect has substantial energetic influence on the nucleation barrier. When considering elastic misfit stresses in nucleation energy calculations, which are expected in the gigapascal range if no plastic relaxation occurs, surface nucleation barriers for forming iron are substantially lower than those in the interior.

Another important microstructure feature is that some remaining inner wüstite regions became increasingly encapsulated by iron. A limited number of delamination features and pores were observed at the hetero-interfaces. The consequence of this composite phase topology is that outbound oxygen transport must proceed through surrounding bulk iron regions. As a result, last reduction stages were relatively slow, and the reduction rate continuously dropped. Such microscopic core-shell behavior differed from reduction behavior in the early wüstite-to-iron transition stage, when numerous delamination features were observed at wüstite/iron hetero-interfaces.

Discussion

The results from our work reveal a large difference in reduction rate and metallization along the pellet radius. This observation raises significant concerns regarding the overall sluggish reduction rate from these gradient effects and the low efficiency obtained with hydrogen use. For decarbonization of the global steel industry using techniques such as HyDR to be reasonable, green hydrogen must be used. This requirement means that beneficial total efficiency and life-cycle assessment regarding carbon footprint require hydrogen produced by sustainable energy sources, making it a very expensive product. Therefore, hydrogen should be used in such reduction processes as efficiently as possible.

Assessment of total HyDR process efficiency requires consideration of not only total energy balance but also total hydrogen consumption efficiency as an essential cost and sustainability factor. Excessive hydrogen consumption directly translates to increased costs and environmental burden, undermining the sustainability argument for the technology.

The large through-pellet gradient of reduction kinetics observed suggests reconsideration of the suitability of current commercial pellet designs or process optimization for HyDR processes. Given the unique physical properties of molecular hydrogen—its smaller molecular size and lower viscosity compared with carbon monoxide or methane—gas transport phenomena in HyDR can be very different from those in processes with carbon-based reductants. Further studies should assess experimentally and theoretically the effect of pellet size, porosity, and microstructure on gaseous percolation. In this assessment, improved characterization of porous structures is highly needed to reveal three-dimensional connectivity of pores, which is important for disentangling percolation paths. With further help from fluid dynamic simulation, underlying gas transport phenomena can be better understood. The gained knowledge will enable knowledge-based pellet design, which will accelerate overall reduction kinetics in HyDR processes.

Conclusions and Outlook

Our studies quantitatively investigate the spatial gradient of microstructure in partially reduced commercial hematite pellets and its influence on reduction kinetics during HyDR. Microstructural analysis along the pellet radius revealed strong heterogeneity of reduction rate. The surface region showed high metallization of 88 volume percent alpha-iron, whereas the center region contained approximately 4 volume percent alpha-iron—a more than twentyfold difference.

Local microstructural analysis further suggested that outbound oxygen diffusion was substantially delayed not only in center areas of pellets but also in sub-surface zones because remaining wüstite islands were encapsulated by iron. Additionally, the observed abundance of defect-mediated transport pathways for fast oxygen diffusion is insufficient to warrant more homogeneous and rapid reduction kinetics.

Further experimental and fluid dynamic simulations should be conducted to better understand the effect of pellet size, porosity, and microstructure on gaseous percolation. The current findings provide guidance for optimization of pellets in terms of size, porosity, and microstructure to meet demands of fast and efficient HyDR, ultimately enabling the industrial implementation of hydrogen-based steelmaking at scale.

The path forward requires integrating these microstructural insights with reactor design innovations and pellet engineering to achieve the hydrogen consumption efficiency and reduction rates necessary for economically viable and environmentally sustainable iron production. Only through such comprehensive optimization can hydrogen-based direct reduction become a viable alternative to carbon-based steelmaking processes.