High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles

Basic considerations about High-Entropy Alloy Nano-Particles

The field of high‑entropy alloy nanoparticles has moved well beyond the early excitement of “mixing five or more elements and letting configurational entropy do the magic.” At the nanoscale, it has become increasingly clear that entropy is often a relatively minor actor. What truly governs phase stability, structure, and functional behavior are kinetic effects, surface reconstruction, segregation, defects, decomposition, and, quite frequently, unnoticed interstitial contamination by light elements such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, boron, or sulfur that are introduced during synthesis or under real operating conditions.

Bulk high‑entropy alloys can sometimes hide behind their mostly single‑phase, metastable appearance and their sluggish diffusion and complex transformation mechanisms. Those features can even be turned into advantages, as shown for mechanically robust, corrosion‑resistant, or magnetically soft bulk HEAs. Nanoparticles, however, enjoy no such luxury. Their enormous surface‑to‑volume ratio, their rapid and often far‑from‑equilibrium synthesis, and their exposure to harsh environments reveal the true thermodynamic and kinetic transience of many reported compositions. Instead of ideal solid solutions, one often encounters decomposition, demixing, surface reconstruction, short‑range ordering, and dynamic ensemble behavior that deviate strongly from the original bulk‑inspired vision.

These pronounced differences between bulk HEAs and nanoscale HEA particles are not a drawback in themselves; they open up a new design space. The key is to embrace them and use them deliberately. Rather than endlessly expanding the list of complex average compositions, the community is now challenged to focus on what actually controls the transient character and stability of these particles, particularly at their surfaces and in realistic environments. That includes exploiting kinetic barriers, short‑range order, defect structures and their chemical decoration, and dynamic surface reconstructions to generate emergent catalytic, magnetic, or corrosion‑related properties that cannot be achieved in conventional nanoscale alloys.

Theory and simulation must therefore move beyond the cubic‑scaling limitations of traditional density functional theory and adopt large‑scale, accurate machine‑learning interatomic potentials and property‑driven screening of the enormous configuration space. Recent progress on high‑throughput, ML‑enabled HEA discovery and on robust strategies for validating machine‑learned potentials points the way towards this next phase. In parallel, synthesis must become far more chemically aware and reproducible, with rigorous control and transparent documentation of interstitials, defect states, and decomposition kinetics during both production and use. Finally, functional assessment can no longer lean primarily on post‑mortem characterization. True operando measurements of reaction zones, ordering, reconstruction, composition, and dynamics of the atomic clusters that actually carry catalytic or magnetic activity are indispensable.

Once HEA nanoparticles are accepted as inherently defect‑rich, surface‑dominated, and kinetically variable objects, more appropriate design metrics are needed. These have to go beyond the simplistic mean‑field measure of bulk configurational entropy and instead reflect kinetic stability, surface defect chemistry, dynamic segregation, and multifunctional performance. The work presented at the Faraday Discussion 2025 suggests that promising opportunities lie, for example, in magnetically active catalysts, noble‑metal‑lean electrocatalysts, and nanoparticles that combine corrosion resistance, thermal stability, and high activity in one material. The road ahead is demanding, but the potential payoff in sustainable catalysis, magnetic applications, and energy‑relevant technologies is substantial. In short, it is time to stop treating high‑entropy nanoparticles as mere miniaturized versions of bulk HEAs and to recognize them as a distinct and fascinating class of materials in their own right.

Faraday Discussions

Raabe Faraday Remarks as published D5FD0[...]

PDF-Dokument [280.0 KB]

Introduction to High‑entropy alloy nanostructures

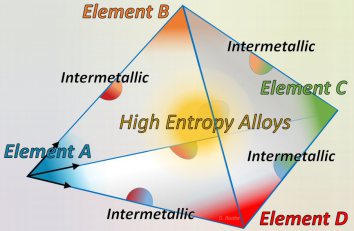

High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs) were originally defined as metallic materials consisting of five or more principal elements mixed in near-equiatomic proportions. The core concept was to exploit high configurational entropy to stabilize solid solutions within simple crystal structures. However, while mixing entropy is important, Gibbs thermodynamics dictates that the total free energy minimum—considering all possible phases—determines equilibrium. Intermetallics often form in these materials after prolonged treatment, suggesting that many reported HEAs exist in a kinetic transient.

This is particularly apparent in nanoparticles, where kinetic effects like fast surface diffusion and thermodynamic effects like the Gibbs-Thomson relation can be more essential for stability than mixing entropy. A "Quo Vadis" analysis for the field suggests revisiting fundamental stability assumptions and adopting a theory-based approach to identify emergent phenomena. We must move past the description of HEAs as "ideal solid solutions" and recognize that HEA nanoparticles are kinetically driven, with performance dictated by local chemical ordering, surface dynamics, and the precise control of structural defects.

Adv. Sci. 2026, 13, e10537

Advanced Science - 2025 - Nallathambi - [...]

PDF-Dokument [2.6 MB]

Theory-Guided Exploration of the Huge Chemical and Structural Configuration Space for High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles

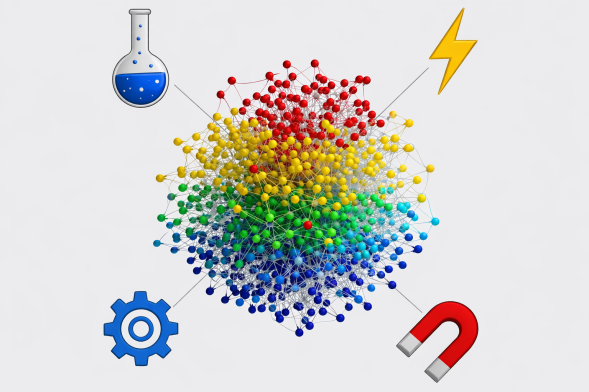

The vastness of the compositional and structural landscape is currently the primary bottleneck preventing the rational design of new HEA systems. Theoretical exploration must move beyond trial-and-error toward AI-guided strategies that account for thermodynamics, kinetics, and synthesis-related contamination. This is a severe challenge; for even a modest system of 100 atoms, the number of possible configurations is astronomical, making exhaustive exploration impossible.

Traditional Density Functional Theory (DFT) is limited by its computational scaling, making the calculation of fundamental properties in large supercells prohibitively expensive. Progress depends on large-scale simulations using GPU-accelerated Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics techniques. Advanced machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) are now essential, as they can reproduce the accuracy of first-principles methods while drastically improving efficiency. These tools allow us to simulate segregation, decomposition, and phase transformations across different time and length scales. Search strategies should also shift toward property-driven metrics—such as magnetic moments or electrochemical parameters—rather than focusing on phase stability alone.

nature reviews materials

Multifunctional high-entropy.pdf

PDF-Dokument [2.2 MB]

Nanoparticle Decomposition and the Interstitial Alloying and Contamination Effects in High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles

In nanostructured HEAs, stability under functional conditions is predominantly kinetic. The primary concern is not just initial phase formation, but the resistance to decomposition and demixing under thermal or electrochemical stress. HEA nanoparticles often operate in metastable states where performance is dictated by kinetic barriers. Designing alloys with tailored short-range ordering (SRO) can enhance these barriers, suppressing defect evolution and improving long-term stability.

A critical source of instability is the presence of unquantified interstitial contaminants like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. These are not simply impurities but inherent components that influence the configuration space of the surface. A lack of rigorous control over these contaminants during synthesis results in low reproducibility. Additionally, in situ studies show that HEA nanoparticles undergo pronounced dynamic instability under reactive conditions, including demixing and void formation. Interestingly, the oxidation rate of HEA nanoparticles is often significantly slower than that of monometallic counterparts because their chemical complexity disrupts fast diffusion pathways. This suggests that researchers should focus on managing nanoscale "defect effects" to achieve superior kinetic stability.

Nature Com 2022 Massive interstitial sol[...]

PDF-Dokument [3.2 MB]

The Surfaces of Functional High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles as Complex Dynamic Ensembles with Multiple Reconstruction Features

The performance of HEA nanoparticles in catalysis and electrochemistry depends on the dynamic state of the surface, which is distinct from the bulk interior. Understanding the relationship between the bulk and the surface is crucial: the active surface structure is highly sensitive to the environment, temperature, and adsorbed species. HEA surfaces are intrinsically susceptible to segregation, which is dynamically induced during operation.

The active state observed during operando conditions often bears little resemblance to the state seen in post-mortem analysis. Capturing this dynamic evolution is vital for developing accurate predictive models. Because of their chemical complexity, HEA surfaces provide a wide diversity of binding sites, meaning adsorption energy cannot be characterized by a single value. The field requires a robust "chemical defect theory" to formalize the role of local chemistry in energetics. Furthermore, we must quantify the thickness of the active reaction interface using advanced operando analysis—coupling high-resolution structural techniques with chemical detection—to validate theoretical models.

Moravcik Interstitial doping enhances th[...]

PDF-Dokument [6.2 MB]

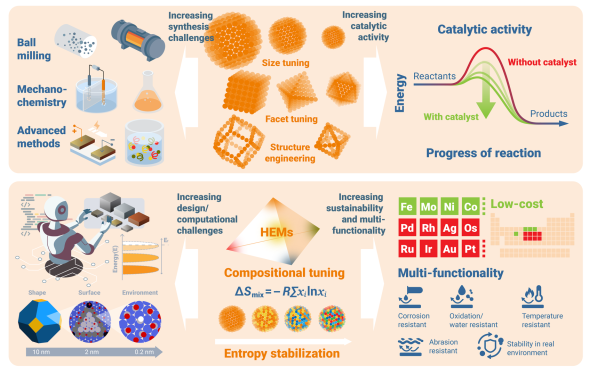

Challenges in the Synthesis of High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles

Advancements in theory and characterization place new demands on synthesis methodology. We must move toward chemically controlled and kinetically informed design with improved reproducibility and impurity control. Synthesizing colloidal HEA nanoparticles is difficult because different constituent metals have unique reactivity profiles and reduction rates. If these aren't synchronized, it leads to compositional gradients and phase separation.

Highly controlled techniques, such as hot-injection synthesis, are essential for achieving monodisperse, ultra-small single-phase particles. Additionally, solution-based approaches like continuous-flow reactors are critical for tuning size and shape while minimizing energy consumption. Addressing interstitial contamination is also vital, as these elements can drastically alter the crystalline state and surface activity of the particles.

A Trajectory Vision: Property-Driven Multifunctionality for High‑Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles

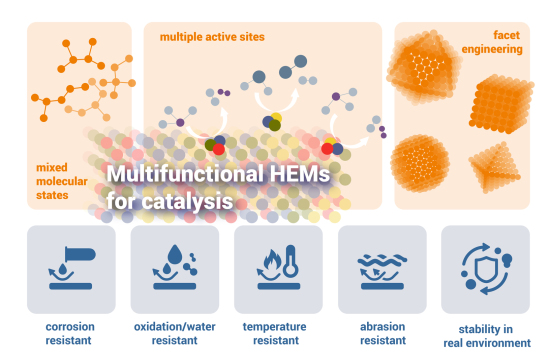

The complexity of HEAs can be exploited to deliver integrated performance metrics that are difficult to attain with conventional alloys. We should aim for multifunctionality, reconciling aspects such as easy synthesis, corrosion resistance, and high catalytic activity in a single material. Examples of this synergy are already emerging, such as magneto-catalysis, where magnetic elements allow for the easy recycling of catalysts.

The HEA strategy also allows for the design of efficient non-noble electrocatalysts, reducing reliance on scarce and expensive elements. Accelerating these designs requires sophisticated AI and machine learning for multi-objective optimization. Finally, future research must align with global societal demands, emphasizing applications like CO2 capture and sustainable energy conversion. Moving away from noble-metal-rich HEAs toward "lean-alloy" designs is a critical path for creating sustainable, high-performance materials.

It is time to stop treating high-entropy nanoparticles as merely miniaturized bulk alloys and start recognizing them as a fascinating and distinct class of materials.