Martensite to austenite reversion steels

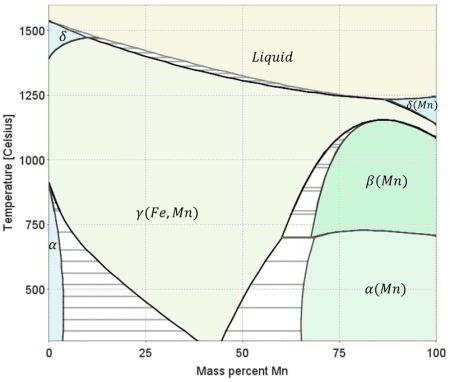

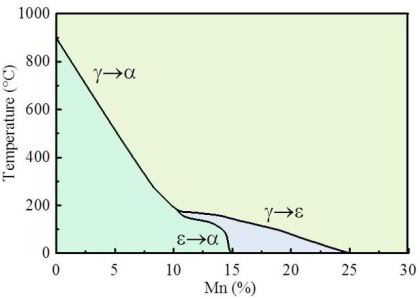

Strong, damage-tolerant, and functional steels are the backbone for innovations in the fields of manufacturing, energy, transportation, and safety. Examples are Fe-Cr steels for emission-reduced turbines; weight reduced and high strength as well as martensite reversion-based Fe-Mn steels for light-weight and safe mobility; magnetic Fe-Si steels for low-loss electrical motors and generators; or stainless steels for nuclear, fusion, and direct solar thermal power plants. These few steel type examples document the necessity of developing improved high strength and yet ductile steels. Most hardening mechanisms, however, such as enabled by solutes, dislocations, or precipitates, albeit leading to high strength, often reduce ductility rendering the material brittle and susceptible to failure. This phenomenon is known as the inverse strength-ductility problem. In this context the reduction of the average grain size offers a pathway for increasing both, strength and toughness of steels. In our studies we try to develop this concept further in that we combine this strategy with the manipulation of the individual interfaces by grain boundary segregation and local phase transformation. Regarding the latter aspect specifically the martensite-to-austenite reversion mechanism is of high interest. More specific, we thus enable grain boundaries in high strength steels not only as barriers against dislocation motion but also as regions where segregation and nanoscale phase transformation can take place. Such locally transformed regions (here: martensite-to-austenite reversion or shorter, martensite reversion / reversed austenite, at martensite grain boundaries) can act as compliance layers or, respectively, mechanical buffer zones impeding for instance crack penetration among lath martensite lamellae. It should be mentioned that for this concept to work the exact nature of the decorated and subsequently transformed martensite grain boundaries is not decisive. Martensite can reveal different types of interfaces which could in principle all be manipulated in the way described, namely, prior austenite, packet, block, or lath boundaries, which have all different energy, structure, misorientation, mechanics, and segregation properties. In the current alloy lath martensite boundaries are the most relevant and frequent types of interfaces. They are preferably susceptible to crack penetration owing to their low mutual misorientation, hence, reversing them into an austenite buffer layer might be of specific benefit in the current alloy design strategy.

Science 349, 1080 (2015)

Linear Complexions: Confined Chemical and Structural States at Dislocations

M. Kuzmina, M. Herbig, D. Ponge, S. Sandlöbes, D. Raabe

Dislocations as Linear Complexions Scien[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.5 MB]

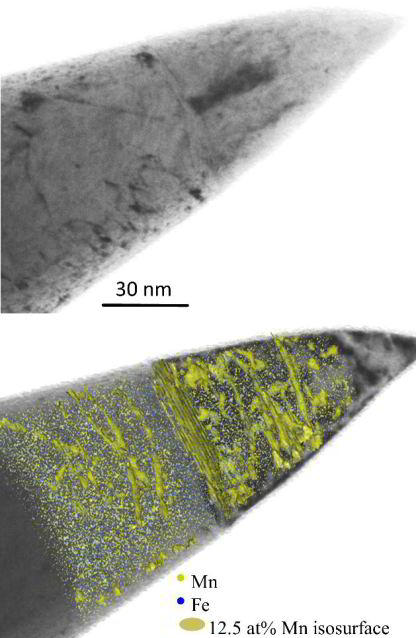

For 5000 years metals are mankind’s most essential materials owing to their ductility and strength. Linear defects called dislocations carry atomic shear steps enabling their formability. We report chemical and structural states confined at dislocations. In a body centered cubic Fe-9at% Mn alloy, we found Mn segregation at dislocation cores during heating followed by formation of face centered cubic regions but no further growth. The regions are in equilibrium with the matrix and remain confined to the dislocation cores with coherent interfaces. The phenomenon resembles interface-stabilized structural states called complexions. A cubic meter of strained alloy contains up to a light-year of dislocation length, suggesting that linear complexions could provide opportunities to nanostructure alloys via segregation and confined structural states.

Structural defects such as interfaces or dislocations in crystalline solid solutions are disturbed regions and attract solute segregation when diffusion is enabled (1-5). According to the Gibbs isotherm the driving force is the reduction of the system’s energy. Extending this concept also to non-isostructural cases suggests that local structural transformations can occur if the chemical composition and stress at a defect reach a level sufficient for stabilizing a state different from the matrix (6,7). The concept of interface complexions (8-17) extends the classical isotherm to interface-stabilized states which have a different structure and composition than the matrix and remain confined in the region where they form. We observed such a phenomenon also at linear defects, i.e. edge dislocations, in a binary Fe-9at%Mn model alloy where a stable face centered cubic (fcc, austenitic) confined structure forms in an otherwise body centered cubic (bcc, martensitic) crystal. This is a phenomenological 1-D analog of the previously observed complexions that were observed at planar defects (8).

We homogenized the Fe-9at%Mn alloy at 1100°C, then quenched and cold rolled it to 50% reduction for increasing the dislocation density. Subsequent annealing at (i) 400°C, 336 hours (2 weeks); (ii)

450°C, 6 hours, 18 hours and 336 hours; and (iii) 540°C, 6 hours enabled Mn diffusion (18). To characterize structure and composition at the same positions, we conducted correlative STEM-APT analysis

(STEM: scanning transmission electron microscopy, APT: atom probe tomography) (19-23). We identified structural defects using STEM and cross-correlated it with solute decoration observed by APT (Fig.

1). Two grain boundaries and a single dislocation line are highlighted by blue arrows in the STEM micrograph and in the 3D atom map where they are visible as Mn-enriched regions. The correlative STEM

experiments clearly identify the linear Mn-enriched features in the APT volumes as dislocations. As evident from the STEM micrograph not all dislocations attract solute segregation high enough to be

detectable by APT (red arrow 1).

We obtained 1-D compositional profiles along cylindrical regions with 1 nm diameter at individual locations (Fig. 1E). Profile #1 shows a concentration of 25±2 at% Mn at the dislocation core, which

corresponds to an enrichment factor of 2.7 compared to the matrix concentration of Mn (9.1 at%). The average thickness of the Mn-enriched zone is about 1 nm. Besides the high Mn content at the

dislocation cores, the composition along the dislocation line (profile #2) reveals periodic Mn changes, i.e. enriched and depleted zones alternating with a spacing of ~5 nm, resembling a nano-sized

pearl necklace.

Raabe et al. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 18 (2014) 253:

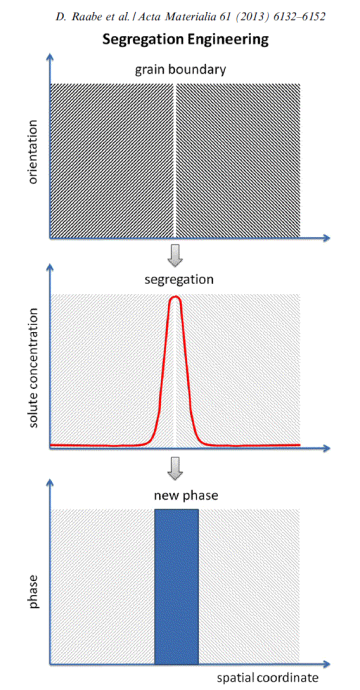

Grain boundaries influence mechanical, functional, and kinetic properties of metallic alloys. They can be manipulated via solute decoration enabling changes in energy, mobility, structure, and cohesion or even promoting local phase transformation. In the approach which we refer here to as ‘segregation engineering’ solute decoration is not regarded as an undesired phenomenon but is instead utilized to manipulate specific grain boundary structures, compositions and properties that enable useful material behavior.

Current Opinion 2014 Grain Boundary Segr[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.7 MB]

Grain boundaries (GBs) are ubiquitous defects in metallic alloys governing a range of properties, such as tensile strength, fatigue resistance, fracture toughness, strain hardening,

brittleness, conductivity, or corrosion [1–7]. Unlike bulk phases they are planar and require 5 parameters to be crystallographically characterized (disorientation, plane inclination).

Hence, they cannot be regarded as scalar objects with homogeneous properties but as a high dimensional class of defects. For example, even for highly coherent GBs such as first order twins

(R3 CSL (coincidence site lattice)) exponential property changes can occur if the GB plane is misaligned by only a few degrees from its most coherent position.

GBs can either weaken (inter-crystalline fracture, stress corrosion cracking) or strengthen (Hall-Petch effect) polycrystalline metallic materials. In either case the types of GBs involved

affect the specific material response substantially as was discussed particularly in the context of highly coherent versus random GBs.

These observations led to the concept of grain boundary engineering which aims at designing polycrystals with specific GB distributions [8–11].

The next logical step in this context lies in also considering and engineering the segregation and its effects on GBs [12–24]. This is an obvious thought since many if not all GB properties

are accessible to decoration-driven manipulation such as cohesion [12–14]; energy [18–23]; fracture resistance [12]; electrical conductivity [25,26]; transport coefficients [27];

electrochemical properties [24,25,28]; hydrogen embrittlement [30,31]; mobility [32–38];

and resistance to or sources of dislocations [47–57] to name only a few effects that are relevant for structural alloys. We refer to such manipulation of GBs via solute decoration

and even confined transformation as ‘grain boundary segregation engineering’ (GBSE) or just ‘segregation engineering’ [58]. Applying

GBSE needs to involve both, thermodynamic (segregation coefficient; co-segregation; competing bulk phases) and kinetic (diffusion) influence factors. Hence, not only the associated

crystallographic degrees of freedom and all segregated elements should be considered but also time and temperature. However, as will be addressed below, GBSE can for a number of alloys even

be applied when knowing the average segregation level to non-ordered or ‘random’ GBs, i.e., a full 5D crystallographic description is not in all cases required. GB segregation changes

with time when the heat treatment or application temperature is high enough for diffusion. Hence, also the GB properties may alter. GBSE considers solute decoration not as an undesired

and inherited phenomenon but instead utilizes segregation as a tool for site-specific manipulation that allows for optimizing specific grain boundary structures,

compositions and properties that enable the design of beneficial material behavior [42–46,58,59]. More specific, GB segregation can be used as a microstructure design method since

solutes affect the structure, phase state and atomic bonds within the decorated interface. Different scenarios are conceivable: first, segregation of certain solutes might enhance GB

cohesion (GB strengthening). Second, the reverse might apply, namely, reduction in cohesion

and bonding strength (interface weakening) at GBs due to segregation. Third, segregation could be strong enough, in conjunction with the available interfacial energy and local stresses, to

result in a phase transformation of or at the GB region [58]. Related to the latter point is the possibility for the formation of complexions, i.e., interface stabilized phases

[60–66]. An important question in that context is the accessibility of these segregation-dependent GB features via an ‘engineering’ approach. Indeed various examples are conceivable

where such misorientation- and plane-sensitive design approach can work, namely, diffusion annealing, grain growth heat treatment, and local phase transformation effects. A

typical example for an engineering heat treatment approach to tune a desired segregation level at GBs lies in a combined diffusion plus grain growth heat treatment: Since the reduction and

GB energy may depend on both, the GB plane inclination and its crystallographic misorientation, such low energy configurations can be obtained for instance by a grain growth heat treatment,

where low-energy interfaces prevail owing to their comparably small capillary driving force. Another broadly applicable example of GB segregation engineering lies in the reduction of

the average grain size due to an overall drop in GB energy caused by equilibrium segregation.

Although GBSE can be applied to such diverse systems as solar cells [67,68], superconductors [69], or ceramics [60–66] we focus here on recent developments pertaining to metallic alloys

used for structural applications [70–82]. In these materials we see particularly high relevance and opportunities of the GBSE concept for designing improved ultra fine grained and

nanostructured metallic alloys where GBs constitute a large fraction of the material. Particularly alloys with nanoscaled grain size suffer often from very low ductility in conjunction

with inter-crystalline damage. In such materials particularly the inter-

nal interfaces are prone to void formation and damage initiation.

Since grain boundaries generally can influence mechanical, functional, and kinetic properties of metallic alloys, they can likewise be manipulated via solute decoration enabling changes in energy, mobility, structure, and cohesion or even

promoting local phase transformation. In the approach which we refer here to as ‘segregation engineering’ solute decoration is not regarded as an undesired phenomenon but is instead utilized to

manipulate specific grain boundary structures, compositions and properties that enable useful material behavior. The underlying thermodynamics follow the adsorption isotherm. Hence,

matrix-solute combinations suited for designing interfaces in metallic alloys can be identified by considering four main aspects, namely, the segregation coefficient of the decorating

element; its effects on interface cohesion, energy, structure

and mobility; its diffusion coefficient; and the free energies of competing bulk phases, precipitate phases or complexions. From a practical perspective, segregation engineering in alloys can be

usually realized by a modest diffusion heat treatment, hence, making it available in large scale manufacturing.

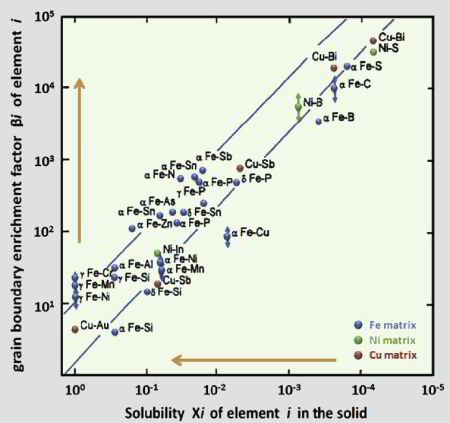

For utilizing this concept we first have to better understand the susceptibility of grain boundaries to solute decoration and the resulting property changes. This phenomenon, referred to as grain boundary segregation, is characterized by the redistribution of solutes from the grain interiors to the grain boundaries. Solute concentrations on grain boundaries can exceed the solubility inside grains sometimes by a factor of 2-3 and sometimes even by more than an order of magnitude. A rough approximation of the segregation tendency of a solute is its inverse bulk solubility, namely, the smaller the bulk solubility, the higher the enrichment factor on the interface. When grain boundary segregation occurs, either via inherited solute decoration from preceding processing (i.e. decoration of former austenite grain boundaries) or upon modest tempering after quenching (i.e. decoration of ferrite or martensite grain boundaries), different scenarios are conceivable: first, segregation might enhance coherence and preferential bonding in the interface (grain boundary strengthening). Second, the reverse might be true, namely, the further loss of coherence and weaker or unfavourably directed bonding in the interface (grain boundary weakening). Third, segregation could lead to phase transformation of the grain boundary (grain boundary phase transformation). Fourth, segregation could promote formation of one or more second phases at the decorated interface (grain boundary precipitation; complexions; phase formation at grain boundaries). Fifth, discontinuous precipitation might be initiated. Besides these possible direct structural changes in the intrinsic grain boundary properties due to segregation, also their energy is affected. Gibbs' adsorption isotherm, when adopted to segregation at internal interfaces, quantifies the reduction in the total system free energy as driving force for equilibrium segregation. Since the bulk grain depletion and the associated free energy change is negligible in this context, the main thermodynamic driving force for segregating solutes to grain boundaries lies in the reduction of the interface free energy. This also affects the relationship between segregation and ductility since a drop in the grain boundary energy reduces the driving force for grain growth. Hence, materials with reduced grain boundary energy can, under the same thermomechanical treatment as used for materials without grain boundary segregation, have a smaller and at the same time rather stable grain size. This can improve both strength and toughness, provided the specific type of segregation does not lead to grain boundary embrittlement. In the present study we address one specific phenomenon, namely, the segregation of solute Mn to martensite grain boundaries. This includes all possible kinds of martensite grain boundaries, i.e., prior austenite boundaries, block boundaries, packet boundaries and lath boundaries of a quenched and tempered Fe-Mn alloy and the associated nanoscale phase transformation of the decorated grain boundary region from martensite to austenite. This martensite-to-austenite reversion occurs at a temperature far below the bulk re-transformation temperature. Such interactions among grain boundary structure, segregation, and confined phase transformation open opportunities for the nanoscale engineering of damage tolerant high strength steels since all these mechanisms can be realized through simple alloying and thermomechanical processing strategies. The challenge here lies in documenting both, segregation and nanoscale phase transformation at the same interface. This requires the combined use of characterization methods with near atomic-scale chemical and structural resolution. Here we use atom probe tomography in conjunction with TEM diffraction. We coin this new approach of jointly manipulating the structure and composition of grain boundaries via segregation plus phase transformation as ‘segregation engineering’.

Acta Materialia 85 (2015) 216-228

Acta Materialia 85 (2015) 216 Nanolamina[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.3 MB]

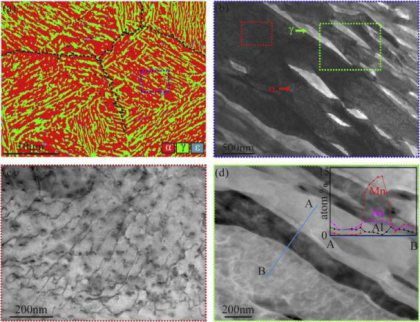

Conventional martensitic steels have limited ductility due to insufficient microstructural strain-hardening and damage resistance mechanisms. It was recently demonstrated that the ductility and

toughness of martensitic steels can be improved without sacrificing the strength, via partial reversion of the martensite back to austenite. These improvements were attributed to the presence of

the transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) effect of the austenite phase, and the precipitation hardening (maraging) effect in the martensitic matrix. However, a full micromechanical

understanding of this ductilizing effect requires a systematic investigation of the interplay between the two phases, with regards to the underlying deformation and damage micromechanisms. For this

purpose, in this work, a Fe–9Mn–3Ni–1.4Al–0.01C (mass%) medium-Mn TRIP maraging steel is produced and heat-treated under different reversion conditions to introduce well-controlled variations in

the austenite–martensite nanolaminate

microstructure. Uniaxial tension and impact tests are carried out and the microstructure is characterized using scanning and transmission electron

microscopy based techniques and post mortem synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis. The results reveal that (i) the strain partitioning between austenite and martensite is governed by a highly

dynamical interplay of dislocation slip, deformation-induced phase transformation (i.e. causing the TRIP effect) and mechanical twinning (i.e. causing the twinning-induced plasticity effect);

and (ii) the nanolaminate microstructure morphology leads to enhanced damage resistance. The presence of both effects results in enhanced strain-hardening capacity and damage resistance, and

hence the enhanced ductility.

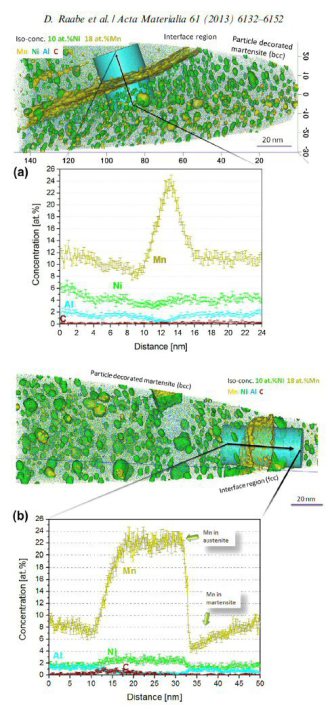

Acta Materialia 61 (2013) 6132-6152: In an Fe–9 at.% Mn maraging alloy annealed at 450 C reversed allotriomorphic austenite nanolayers appear on former Mn decorated lath martensite boundaries. The austenite films are 5–15 nm thick and form soft layers among the hard martensite crystals. We document the nanoscale segregation and associated martensite to austenite transformation mechanism using transmission electron microscopy and atom probe tomography. The phenomena are discussed in terms of the adsorption isotherm (interface segregation) in conjunction with classical heterogeneous nucleation theory (phase transformation) and a phase field model that predicts the kinetics of phase transformation at segregation decorated grain boundaries. The analysis shows that strong interface segreg

Raabe Acta Materialia 2013 Nanoscale-aus[...]

PDF-Dokument [6.0 MB]

Acta Materialia 59 (2011) 364-374: Partitioning at phase boundaries of complex steels is important for their properties. We present atom probe tomography results across martensite/austenite interfaces in a precipitation-hardened maraging-TRIP steel (12.2 Mn, 1.9 Ni, 0.6 Mo, 1.2 Ti, 0.3 Al; at.%). The system reveals compositional changes at the phase boundaries: Mn and Ni are enriched while Ti, Al, Mo and Fe are depleted. More specific, we observe up to 27 at.% Mn in a 20 nm layer at the phase boundary. This is explained by the large difference in diffusivity between martensite and austenite. The high diffusivity in martensite leads to a Mn flux towards the retained austenite. The low diffusivity in

the austenite does not allow accommodation of this flux. Consequently, the austenite grows w

Acta Materialia atom probe tomography st[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.3 MB]

Steels containing reverted nanoscale austenite islands or films dispersed in a martensitic matrix show excellent strength, ductility and toughness. The underlying microstructural mechanisms responsible for these improvements are not yet understood, but are observed to be strongly connected to the cRN island or film size. Two main micromechanical effects are conceivable in this context, namely: (i) interaction of cRN with microcracks from the matrix (crack blunting or arresting); and (ii) deformation-induced phase transformation of cRN to martensite (TRIP effect). The focus here is on the latter phenomenon. To investigate size effects on cRN transformation independent of other factors that can influence austenite stability (composition, crystallographic orientation, defect density, surround

Wang et al Acta Materialia 79 (2014) 268[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.2 MB]

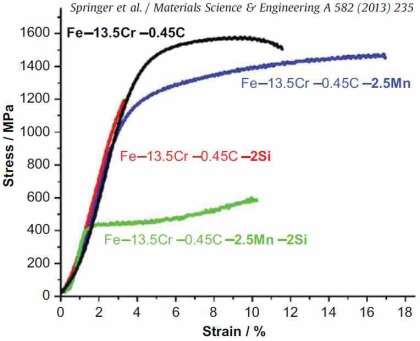

Austenite reversion during tempering of a Fe–13.6 Cr–0.44 C (wt.%) martensite results in an ultra-high-strength ferritic stainless steel with excellent ductility. The austenite reversion mechanism is coupled to the kinetic freezing of carbon during low-temperature partitioning at the interfaces between martensite and retained austenite and to carbon segregation at martensite–martensite grain boundaries. An advantage of austenite reversion is its scalability, i.e. changing tempering time and temperature tailors the desired strength–ductility profiles (e.g. tempering at 400 C for 1 min produces a 2 GPa ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and 14% elongation while 30 min at 400 C results in a UTS of 1.75 GPa with an elongation of 23%). The austenite reversion process, carbide precipitation

Acta-2012-Austenite-reversion-Fe-Cr-C.pd[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.9 MB]

The effect of local martensite-to-austenite reversion on microstructure and mechanical properties was studied with the aim of designing ductile martensitic steels using a combinatorial approach with tensile and hardness testing.

Mater_Sc_Engin_A_582_(2013)_235_bulk com[...]

PDF-Dokument [562.5 KB]

Acta Materialia 86 (2015) 1-14

Acta Materialia 86 (2015) multiphase mic[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.6 MB]

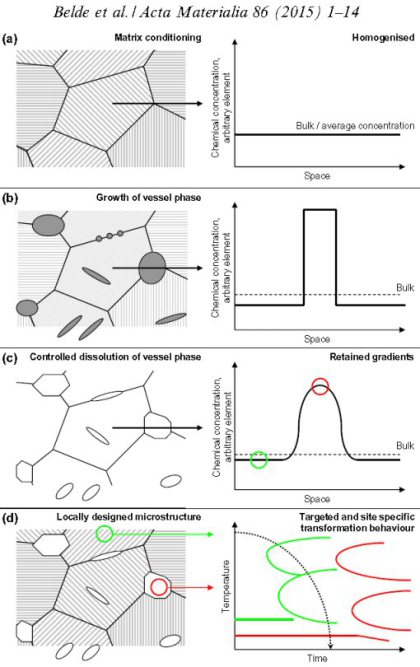

Here we present a novel method to locally control the constitution, morphology, dispersion and transformation behavior of multiphase materials. The approach is based on the targeted, site-specific

formation and confined dissolution of precipitated carbides or intermetallic phases. These dispersoids act as “vessels” or “containers” for specific alloying elements forming controlled chemical

gradients within the microstructure upon precipitation and subsequent (partial) dissolution at elevated temperatures. The basic processing sequence consists of three subsequent steps, namely:

(i) matrix homogenization (conditioning step); (ii) nucleation and growth of the vessel phases (accumulation step); and (iii) (partial) vessel dissolution (dissolution step). The vessel

phase method offers multiple pathways to create dispersed microstructures by the variation of plain thermomechanical parameters such as time, temperature and deformation. This local

microstructure design enables us to optimize the mechanical property profiles of advanced structural materials such as high strength steels at comparatively lean alloy compositions. The approach

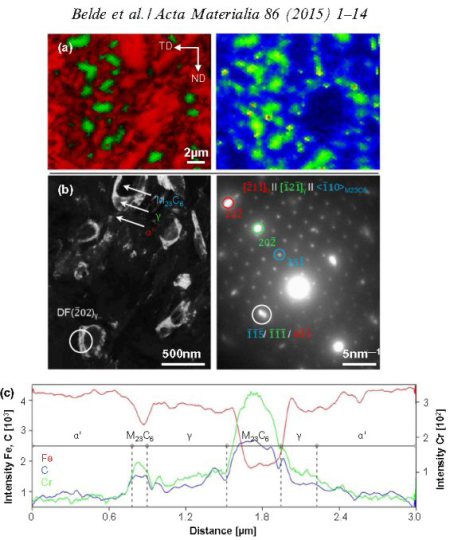

is demonstrated on a

11.6Cr–0.32C (wt.%) steel, where by using M23C6 carbides as a vessel phase, Cr and C can be locally enriched so that the thus-lowered martensite start temperature allows the formation of a

significant quantity of retained austenite (up to 14 vol.%) of fine dispersion and controlled morphology. The effects of processing parameters on the obtained microstructures are investigated,

with a focus on the dissolution kinetics of the vessel carbides. The approach is referred to as vessel microstructure design.