Crystallographic Textures of DP steels (dual phase steels)

What is crystallographic texture?

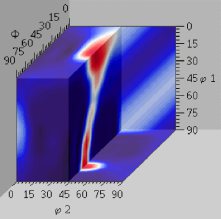

The term crystallographic texture refers to the entity of all orientations and all associated crystallographic orientation aspects of the crystal lattice in crystalline and polycrystalline aggregates. Both, polycrystallien steels and deformed grains do have textures (microtextures, respectively).

A specimen in which these crystal orientations are fully random is said to have no distinct texture or a 'random texture'. If the crystallographic orientations are not random, but have some preferred orientations that prevail, then the sample has a weak, moderate or strong texture, respectively. The degree is dependent on the percentage of crystals having the preferred orientation. Texture is seen in almost all engineered materials, and can have a great influence on materials properties.

How can a crystallographic texture be determined?

The crystallographic texture of a sample can be determined by various types of diffraction methods that typically exploit the constructive interferrence of electromagnetic or electronic waves at groups of lattice planes. Some methods allow a quantitative analysis of the texture, while others are rather qualitative. Among the quantitative techniques, the most widely used is X-ray diffraction using texture goniometers, followed by the EBSD method (electron backscatter diffraction) in Scanning Electron Microscopes. Qualitative analysis can be done by Laue photography, simple X-ray diffraction or with a polarized microscope. Neutron and synchrotron high-energy X-ray diffraction are suitable for determining textures of bulk materials and in situ analysis, whereas laboratory x-ray diffraction instruments are more appropriate for analyzing textures of thin films.

Why are crystallographic textures important ?

Many material properties are anisotropic (direction dependent) already at the lattice structure / single crystal scale. Hence, if preferred orientation alignment prevails in a sample, so are the net / intergal properties of polycrystals.

Particularly material properties such as elastic anisotropy, yield and tensile strength, chemical reactivity, corrosion, sheet forming behaviour and magnetic susceptibility can be highly dependent on the material’s crystal texture.

In many materials, properties are texture-specific, and development of unfavorable textures when the material is fabricated or in use can create weaknesses that can initiate or exacerbate failures.

Consequently, consideration of textures that are present in and that could form in engineered components while in use can be a critical when making decisions about the selection of some materials and methods employed to manufacture parts with those materials.

Typical examples where crystallographic textures are relevant for material properties

In manufacturing and product design textures matter particularly for the anisotropy of the mechanical formability of many metallic materials. An often cited example of this is the earing formation (in-plane sheet shape anisotropy) evolving during deep drawing and stretching operations of sheet metal, as well as the anisotropy of the magnetic properties of practically all soft magnetic (e.g. grain-oriented dynamo and transformer sheet, such as used in the engines and charging infrastructures of / for electric vehicles) and hard magnetic materials (e.g. anisotropic alnico magnets, samarium-cobalt alloys, anisotropic neodymium-iron-boron alloys, hard magnetic ferrites).

What is a dual phase steel (DP steel) ?

The notion DP steel (dual-phase steel) refers to all steels whose microstructure consists of a ferritic (soft) matrix in which a predominantly martensitic (strength-increasing) second phase is embedded in an island shape.

Depoendiung on the volume fraction of the harder phase (scaling the strength) percolation may occur. The proportion of martensite is between 10 and 40 %. With higher martensite content, a higher tensile strength can be achieved, but the elongation to fracture drops.

Materials with such microstructures have relatively low yield strength, which is favourable for the forming process, and high tensile strength, elongation and n-value. These properties are advantageous for complex deep-drawn parts. In addition, DP steel has a pronounced bake-hardening effect. Typical applications for these steels are flat stretch-formed profiles in car doors, strength-relevant carrier structures and energy-absorbing components as well as steel rims.

In DP steels it is an important to measure and to design properties through textures and microstructure features during processing.

How are DP steels made? What is the processing of DP steels?

In order to produce DP steel, it must first be heated or cooled in the two-phase area. Then one has to wait until the desired proportions of austenite (and the desired partitioning of carbon and manganese) and ferrite are obtained. Then cooling is carried out quickly, which transforms the austenite portion into hard martensite (depedning on the carbon content that is quenchedi in). The process can be carried out from the rolling heat by cooling from the γ (austenite phase) area to the two-phase area or by heating from room temperature to the α+γ area.

Dependence of textures of DP steels on processing parameters

In a set of projects we conducted systematic through-process analysis studies of the crystallographic texture evolution in DP steels.

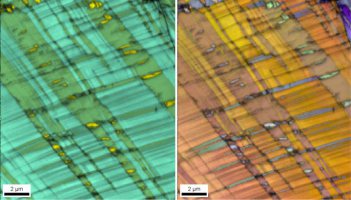

By using SEM/EBSD the substructure and texture evolution in dual phase steels in the first

steps of the process chain, i.e. hot rolling, cold rolling, and following annealing were characterized.

The starting material was hot rolled steel with a chemical composition consisting of 0.147 wt. % C, 1.9 wt. % Mn, 0.4 wt. % Si.

In order to obtain dual phase steels with high ductility and high tensile strength an industrial process was reproduced by cold rolling of industrially hot rolled steel sheets of a thickness of 3.75

mm with ferrite and pearlite morphology down to a thickness of 1.75 mm and finally annealing at different temperatures. Such technique allows a compilation of ferrite and martensite morphology

typical for dual phase steels. Due to the competition between recovery, recrystallization and phase transformation during annealing a variety of ferrite martensite morphologies was produced by

promoting one of the mechanisms through the variation of technological parameters such as heating rate, intercritical annealing temperature, annealing time, cooling rate and the final annealing

temperature. Annealing induced changes of the mechanical properties were determined by hardness measurements and are discussed on the basis of the results of the substructure investigations.

We found that in hot rolled sheets, ferrite and pearlite showed a band structure in the center and a heterogeneous distribution at the surface of the sheet. Texture analysis yielded a

through-thickness texture inhomogeneity and a maximum plane-strain texture in the center and a maximum shear texture close to the surface of the sheet. Due to cold rolling the in-grain orientation

gradients also increased, which is related to an increase of dislocation density and thereby an increase of the driving force for recrystallization. The through-thickness texture inhomogeneity was

reduced by cold rolling.

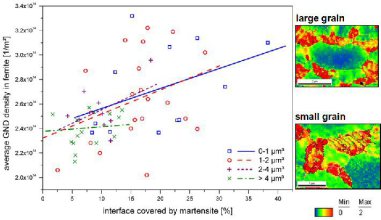

Recovery and recrystallization were found to be dominant for annealing at ferritic temperatures and at low intercritical temperatures up to 695 °C. There is an overlap of recrystallization and phase

transformation only at intercritical annealing temperatures exceeding 740 °C. A correlation between

the volume fraction of martensite and hardness was observed at an intercritical annealing temperature of 740 °C. Increasing the annealing time leads to an increasing martensite fractions and

therefore to an increasing hardness.

Overview Dual Phase Steels Texture Throu[...]

PDF-Dokument [852.2 KB]

Which texture and microstructure parameters are important to measure for dual phase steels in a through-process analysis?

By using EBSD the substructure and texture evolution in dual phase steels in the first steps along the process chain, i.e. hot rolling, cold rolling, and following annealing can be

characterized.

In order to obtain dual phase steels with high ductility and high tensile strength an industrial process can be reproduced at laboratory (or real) scale by cold rolling of industrially hot

rolled steel sheets of a thickness of 3.75 mm with

ferrite and pearlite morphology down to a thickness of 1.75 mm and finally annealing at different temperatures. Such technique allows a compilation of ferrite and martensite morphology typical

for dual phase steels.

Due to the competition between recovery, recrystallization and phase transformation during annealing a variety of ferrite martensite morphologies was produced by promoting one of the

mechanisms through the variation of technological parameters such as heating rate, intercritical annealing temperature, annealing time, cooling rate and the final annealing

temperature.

Annealing induced changes of the mechanical properties were determined by hardness measurements and are discussed on the basis of the results of the substructure investigations.

Two plain carbon steels with varying manganese content (0.87 wt pct and 1.63 wt pct) were refined to approximately 1 lm by large strain warm deformation and subsequently subjected to intercritical annealing to produce an ultrafine grained ferrite/martensite dual-phase steel. The influence of the Mn content on microstructure evolution is studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Metallurgical Transactions A Mn effeect [...]

PDF-Dokument [971.0 KB]

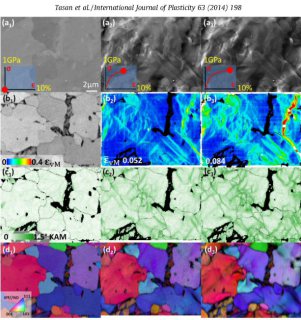

Microstructures of multi-phase alloys undergo morphological and crystallographic changes upon deformation, corresponding to the associated microstructural strain fields. The multiple length and time scales involved therein create immense complexity, especially when microstructural damage mechanisms are also activated. An understanding of the relationship between microstructure and damage initiation can often not be achieved by post-mortem microstructural characterization alone. Here, we present a novel multi-probe analysis approach. It couples various scanning electron microscopy methods to microscopic-digital image correlation (l-DIC), to overcome various challenges associated with concurrent mapping of the deforming microstructure along with the associated microstrain fields.

Yan Tasan Raabe DP steel damage criteria[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.7 MB]

An ultrafine grained (UFG) ferrite/cementite steel was subjected to intercritical annealing in order to obtain an UFG ferrite/martensite dual-phase (DP) steel. The intercritical annealing parameters, namely, holding temperature and time, heating rate, and cooling rate were varied independently by applying dilatometer experiments. Microstructure characterization was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and high-resolution electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). An EBSD data post-processing routine is proposed that allows precise distinction between the ferrite and the martensite phase. The sensitivity of the microstructure to the different annealing conditions is identified.

ISIJ International Vol 52 (2012) 874 ult[...]

PDF-Dokument [514.4 KB]

Autogeneous laser beam welding is an efficient process to join ferritic-martensitic dual-phase steels without large dimensional distortions. Localized softening may occur in the heat affected zone, particularly in DP1000 steel with a high martensite volume fraction. DP1000 steel was welded in bead-on-plate configuration varying the welding power between 0.4 and 2.0 kW and the welding speed between 20 and 150 mm/s. Light optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction were used to perform the microstructural characterization of the welded joints. High-quality laser beam welds of thin sheets of DP1000 steel can be produced using appropriate welding parameters. The optimal welding condition was a nominal laser power of 2.0 kW and a welding speed of 150 mm/s. This co

Dual Phase Steel Laser Beam welding micr[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.7 MB]