Crystallographic Textures of Polycrystalline Metals and Alloys

The Scientific Foundations and Evolution of Crystallographic Texture

Crystallographic texture describes the statistical distribution of crystal lattice orientations within a polycrystalline aggregate, serving as a critical bridge between microscopic lattice arrangements and macroscopic material performance. In an idealized isotropic material, all crystallographic orientations are equally probable; however, in nearly all engineered metals and alloys, thermomechanical processing—such as rolling, extrusion, forging, or drawing—as well as solidification and phase transformations, biases this distribution. This deviation from randomness results in a preferred orientation, a structural state that governs the degree of anisotropy across a wide spectrum of material properties, including mechanical behavior, formability, fatigue resistance, and functional characteristics like magnetic performance.

The significance of texture arises from the inherent anisotropy of the constituent single crystals. Properties such as Young’s modulus, yield strength, strain hardening, and ductility vary significantly depending on the crystallographic direction. When these grains align preferentially, their individual anisotropic behaviors coalesce into a directionally dependent macroscopic response. Consequently, texture development is not merely a byproduct of fabrication but is intrinsically linked to the deformation mechanisms and microstructural evolution occurring during processing. By understanding these evolutionary pathways, metallurgists can optimize process parameters to deliberately engineer specific material properties for targeted applications.

Historically, the scientific investigation of texture emerged in the early twentieth century, driven by the need to optimize iron and steel sheets for electromagnetic applications. Early efforts were largely qualitative, relying on visual inspections of pole figures. The field underwent a paradigm shift in the 1960s when Hans Joachim Bunge introduced the mathematical formalism for quantitative texture analysis. This advancement enabled the transition from descriptive observations to rigorous numerical representations, specifically through the development of the Orientation Distribution Function (ODF), which provides a complete statistical description of the orientation space.

Today, the landscape of texture research is a multi-scale discipline characterized by the integration of four primary pillars:

-

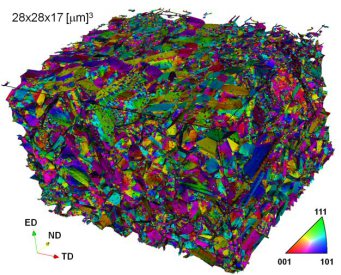

Experimental Quantification: Utilizing advanced diffraction-based techniques (X-ray, neutron, and electron) and high-resolution orientation mapping, such as Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD).

-

Mathematical Representation: The use of ODFs to provide a continuous and quantitative map of orientation density.

-

Predictive Modeling: The application of crystal plasticity frameworks to simulate how texture evolves under complex loading conditions.

-

Property Prediction: Establishing the constitutive laws that link orientation distributions to the final macroscopic behavior of the material.

By synthesizing these theoretical foundations and computational approaches, modern materials science can treat crystallographic texture as a tunable parameter, ensuring that the final product meets the rigorous demands of contemporary engineering.

What Texture Is and Why It Matters

Describing Texture: Pole Figures, ODFs, and Key Components

-

Pole figures (PFs): These are stereographic projections showing the distribution of a given crystallographic pole (e.g., {111} in fcc, {0001} in hcp) relative to sample coordinates (rolling direction RD, transverse direction TD, normal direction ND). Pole figures are intuitive, widely used in sheet metallurgy, and directly relate to anisotropy in forming.

-

Orientation Distribution Function (ODF): The ODF provides a complete, quantitative description of the probability density of orientations in orientation space (often parameterized by Euler angles). ODFs allow the identification and quantification of “texture components” and fibers and enable computation of macroscopic properties through homogenization models.

-

Inverse pole figures (IPFs): These indicate which crystal directions align with a chosen sample direction, often used in EBSD maps to visualize grain orientation.