Which steel compositions are suited for weigth reduced alloy design?

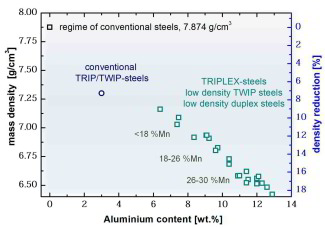

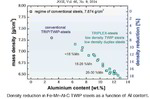

Most steels in this alloy category are in the System Fe-Mn-Al-C-Si. Specifically high-Mn steels attract much attention as lightweight steels due to their outstanding combination of strength and ductility caused by their high strain hardening capacity. Weight reduced variants of these high manganese austenitic steels are typically characterized by high manganese content (18 to 30 wt.%) and the addition of aluminum (< 12 wt.%) and silicon (< 3 wt.%) along with a relatively high content carbon (0.6-1.8 wt.%). As the increase in the aluminum content yields a reduction in the alloy's mass density by 1.5 % per 1 wt.% Al, high aluminum contents render these alloys lightweight.

Why are Al-containing high Mn steels of interest ?

Al-containing, high-Mn steels are characterized by an excellent combination of strength and ductility enabled by their high work hardening capacity. The solute addition of aluminum reduces

the specific weight of the alloy, hence supporting the notion of lightweight and weight reduced high-Mn steels. Increasing the aluminum content by 1 wt.% yields a reduction in

specific weight by about 1.5%. High-Mn lightweight steels usually contain a high content of manganese (18e30 wt.%), aluminum (<12 wt.%) and silicon (<3 wt.%) along with

additions of

carbon (0.6e1.8 wt.%). The precipitation characteristics in the Fe-Mn-Al-C system have been investigated in detail in the last decades for instance by using atom probe tomography and

correlative TEM studies. Due to the strong increase in yield strength in conjunction with a well-maintained tensile ductility upon annealing, the high-Mn lightweight steel systems are

promising lightweight steel candidates for the manufacturing of high performance components.

Which types of strain hardening mechanisms occur in high manganese steels?

A variety of strengthening and strain hardening mechanisms have been reported in high-Mn steels.

These are:

transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP)

twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP)

microband-induced plasticity (MBIP)

dynamical slip band refinemennt

precipitation hardening by kappa carbides

How do the strain hardening mechanisms in high manganese steels depend on the stacking fault energy?

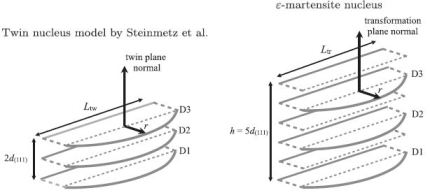

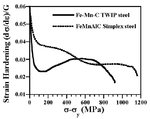

The activation of the prevalent deformation mechanism is mainly determined by the stacking fault energy (SFE). The TRIP effect is found to operate predominantly in low-SFE steels (< 20 mJ m-2). The deformation behavior of medium-SFE steels (20-40 mJ m-2) is characterized by the formation of nanometer thin deformation twins in the deformed microstructure, referred to as TWIP effect. The recently discussed MBIP hardening mechanism, reported in high-SFE alloys (~90 mJ m-2), is described by the formation of thin planar shear zones that are confined by a dislocation wall on either side. These features are called microbands. All the above mentioned hardening mechanisms result in strong refinement of the respective microstructures upon straining enabling high strain hardening rates.

Understanding the relationship between the stacking-fault energy (SFE), deformation mechanisms, and strain-hardening behavior is important for alloying and design of high-Mn austenitic transformation and twinning-induced plasticity (TRIP/TWIP) steels. The present study investigates the influence of SFE on the microstructural and strain-hardening evolution of three TRIP/TWIP alloys.

Pierce Acta Materialia 100 (2015) 178 st[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.5 MB]

Can the TWIP and the TRIP effects occur simultaneously in high manganese steels?

Yes, twinning induced plasticity (TWIP) and transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) can occur in the same alloy depending on the stacking fault energy, on the substructure, on and the thermo-mechanical loading situation (stress, strain, strain rate, temperature, dissiptation rate) and on the transformation free energy difference associated with the transformation between the face centred cubic austenitic phase on the one hand and the hexagonal epsilon phase on the other hand.

Acta Materialia 118 (2016) 140-151: A dislocation density-based crystal plasticity model incorporating transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) is presented. It is a mechanism oriented model which reflects microstructure investigations of ε-martensite, twins and dislocation structures in high

manganese steels. Validation of the model was conducted using experimental data for a TRIP/TWIP Fe-22Mn-0.6C steel. The model is able to predict, based on the difference in the stacking fault energies, the activation of TRIP and/or TWIP deformation mechanisms at different temperatures.

crystal plasticity twinning and TRIP Act[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.5 MB]

Acta Materialia 61 (2013) 494-510: The paper presents a multiscale dislocation density-based constitutive model for the strain-hardening behavior in twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) steels. The approach is a physics-based strain rate- and temperature - sensitive model which reflects microstructural investigations of twins and dislocation structures in TWIP steels. One distinct advantage of the approach is that the model parameters, some of which are derived by ab initio predictions, are physics-based and known within an order of magnitude.

Acta-Materialia-Vol-61-2013-modeling-TWI[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.8 MB]

Which other strain hardening mechanisms are in Fe - high manganese and lightweight steels influenced by the stacking fault energy?

The SFE not only has a strong influence on the deformation mechanism, but it also controls the glide mode of the dislocations. A high SFE usually promotes cross-slip of dislocations leading to “wavy glide” in pure fcc metals. However, in concentrated solid solutions with high SFEs planar glide instead of wavy glide is frequently observed. The reasons for planar glide in such massively alloyed high-SFE materials have been controversially discussed. In the quaternary FeMnAlC system aluminum increases the SFE on the one hand but yet promotes planar dislocation glide on the other hand. Many authors attributed this seemingly contradicting finding to the material’s tendency to form clusters of short-range order (SRO), which leads to enhanced planar glide due to the glide plane softening phenomenon. As the addition of aluminum in these alloys promotes the formation of ordered precipitates (κ-carbides), SRO indeed seems to be a plausible explanation. However, to the authors’ best knowledge no studies providing experimental proof for SRO in high-Mn lightweight steels have been published so far. Some works though indicate the presence of SRO in the FeMnAlC system and similar alloy systems by using density functional theory (DFT) simulations.

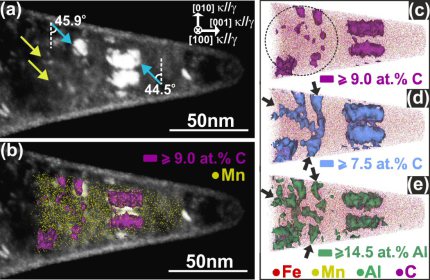

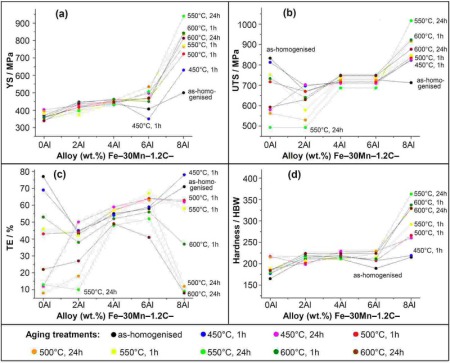

What is the role of the kappa ( κ ) - carbides in high manganese weight reduced steels?

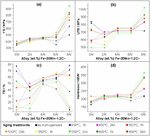

The κ-carbide is a non oxidic perowskite type compound, i.e. a L’12-ordered phase with the stoichiometric composition (Fe,Mn)3AlC. However, κ-carbides exist at a broad compositional range and

coherency strains have an additional influence on their composition. Depending on the aluminum concentration these ordered precipitates either grow during annealing at temperatures between 550°C and

700°C (<10 wt.% Al) or even during quenching from solution heat treatment temperature (>10 wt.% Al). Due to the strong influence of these precipitates on the mechanical properties the

precipitation kinetics have been subject of several studies.

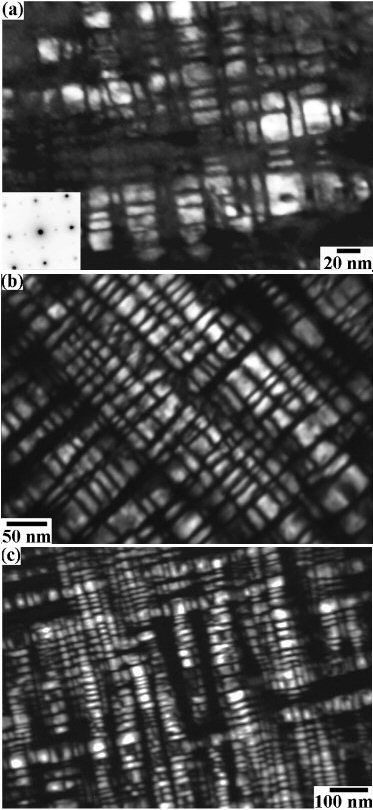

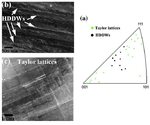

A detailed quantitative characterization of the underlying kinetics of the substructure evolution in the FeMnAlC system has been performed in the case of Fe-30.5Mn-2.1Al-1.2C. With a SFE of about 63

mJ m-2, this alloy, however, falls in the regime between TWIP and MBIP alloys. Yoo et al. investigated the plastic deformation of Fe-28.2Mn-9.95Al-0.98C (wt.%) with a SFE of 120 mJ m-2 and

Fe-27.8Mn-9.1Al-0.79C (wt.%) with a SFE of 85mJ m-2 rendering both alloys pure MBIP steels. They attribute the high strain hardening capacity to the formation of Taylor-lattices and microbands

upon straining. However no quantitative results were presented. Furthermore the formation of microbands have been doubted of causing the observed strain hardening rate in the

literature.

We report on the strengthening and strain hardening mechanisms in an aged high-Mn lightweight steel (Fe-30.4Mn-8Al-1.2C, wt.%) studied by electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), atom probe tomography (APT) and correlative TEM/APT.

Acta Mater 2017 precipitation hardened w[...]

PDF-Dokument [7.5 MB]

Scripta Materialia 68 (2013) 348-353: Here we study the structure and chemical composition of the kappa-carbide formed as a result of isothermal transformation in an

Fe–3.0Mn–5.5Al–0.3C alloy using transmission electron microscopy and atom probe tomography. Both methods reveal the evolution of kappa-particle morphology as well as the partitioning of solutes. We propose that the j-phase is formed by a eutectoid reaction associated with nucleation growth. The nucleation of j-carbide is controlled by both the ordering of Al partitioned to austenite and the carbon diffusion at elevated temperatures.

Scripta Materialia 68 (2013) 348–353 car[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.0 MB]

Acta Materialia 106 (2016) 229-238: Here we report on the investigation of the off-stoichiometry and site-occupancy of k-carbide precipitates within an austenitic, Fe-29.8Mn-7.7Al-1.3C (wt.%) alloy using a combination of atom probe tomography

and density functional theory. The chemical composition of the k-carbides as measured by atom probe tomography indicates depletion of both interstitial C and substitutional Al, in comparison to the ideal stoichiometric L012 bulk perovskite.

Acta Materialia 106 (2016) 229 Kappa car[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.2 MB]

Acta Materialia 116 (2016) 188-199

Acta Materialia 116 (2016) 188 Dynamic S[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.1 MB]

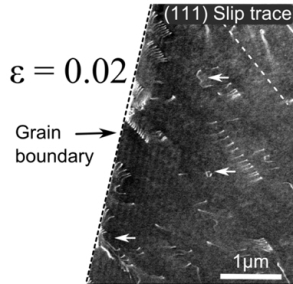

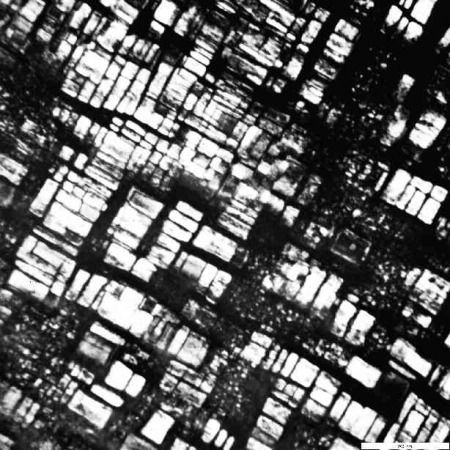

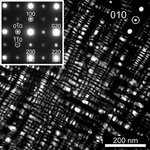

The strain hardening mechanism of a high-Mn lightweight steel (Fe-30.4Mn-8Al-1.2C (wt%)) is investigated by electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) and transmission electron microscopy

(TEM). The alloy is characterized by a constant high strain hardening rate accompanied by high strength and high

ductility (ultimate tensile strength: 900 MPa, elongation to fracture: 68%). Deformation microstructures at different strain levels are studied in order to reveal and quantify the governing

structural parameters at micro- and nanometer scales. As the material deforms mainly by planar dislocation slip causing the

formation of slip bands, we quantitatively study the evolution of the slip band spacing during straining. The flow stress is calculated from the slip band spacing on the basis of the passing

stress. The good agreement between the calculated values and the tensile test data shows dynamic slip band refinement as the main strain hardening mechanism, enabling the excellent

mechanical properties. This novel strain hardening mechanism is based on the passing stress acting between co-planar slip bands in contrast to earlier attempts to explain the strain

hardening in high-Mn lightweight steels that are based on grain subdivision by microbands.We discuss in detail the formation of the finely distributed slip bands and the gradual reduction

of the spacing between them, leading to constantly high strain hardening. TEM investigations of the precipitation state in the as-quenched state show finely dispersed atomically

ordered clusters (size < 2 nm). The influence of these zones on planar slip is discussed.

Ti-bearing lightweight steel with large high temperature ductility via thermally stable multi-phase microstructure

We developed a novel Ti-bearing lightweight steel (8% lower mass density than general steels), which exhibits an excellent combination of strength (491 MPa ultimate tensile strength) and tensile ductility (31%) at elevated temperature (600 °C). The developed steel is suitable for parts subjected to high temperature at reduced dynamical load. The composition of the developed steel (Fe–20Mn–6Ti–3Al–0.06C–NbNi (wt%)) lends the alloy a multiphase structure with austenite matrix, partially ordered ferrite, Fe2Ti Laves phase, and fine MC carbides. At elevated temperature (600°C), the ductility of the new material is at least 2.5 times higher than that of conventional lightweight steels based on the Fe–Mn–Al system, which become brittle at elevated temperatures due to the inter/intragranular precipitation of κ-carbides. This is achieved by the high thermal stability of its microstructure and the avoidance of brittle κ-carbides in this temperature range.

Materials Science & Engineering A 808 (2021) 140954

MSE A 2021 Ti-bearing lightweight steel.[...]

PDF-Dokument [7.9 MB]

Why is electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) well suited for studying low density steels?

We study the microstructures in such alloys by means of electron channeling contrast imaging (ECCI) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The combination of these two techniques constitutes a powerful method for giving insight into the underlying mechanisms of plastic deformation at different length scales. The TEM investigation focuses on the initial precipitation state, whereas the large field of view provided by ECCI provides statistical and quantitative data on the structural evolution of deformation features. High-magnification ECCI was used to provide details on the observed dislocation arrangements on the finer scale. In this study the applied ECCI technique exhibits an advantage over the commonly used TEM imaging in terms of sample dimensions, field of view, preparation artifacts and image forces. As TEM samples have a thickness of about 100 nm, dislocations in the sample can change their position due to image forces originating from the two surfaces of the thin foil or from bending. In contrast, ECCI is applied to bulk samples with only one polished surface. Therefore, deformation microstructures that are characteristic of the actual bulk material are investigated rather than relaxed dislocation structures influenced by stress relaxation. In the case of ECCI the image forces from the surface reach less than 20 nm into the sample, while the depth of observation is of the order of 100 nm. Dislocations will therefore not rearrange as strongly as in TEM thin foils, which enables investigation of the undistorted dislocation structure of bulk samples.

JOM, Vol. 66, No. 9, 2014:

Recent developments in the field of austenitic steels with up to 18% reduced mass density. The alloys are based on the Fe-Mn-Al-C system. Here, two steel types are addressed. The first one is a class of low-density twinning-induced plasticity or single phase austenitic TWIP (SIMPLEX) steels with 25–30 wt.% Mn and<4–5 wt.% Al or even<8 wt.% Al when naturally aged. The second one is a class of j-carbide strengthened austenitic steels with even higher Al content. Here, j-carbides form either at 500–600°C or even during quenching for >10 wt.% Al. Three topics are addressed in more detail, namely, the combinatorial bulk high-throughput design of a wide range of corresponding alloy variants, the development of microstructure–property relations for such steels,

JOM, Vol. 66, No. 9, 2014 page 1845 Low-[...]

PDF-Dokument [3.2 MB]

Low density Fe-Mn-Al-C austenitic steels / Weight reduced austenitic steels

Reducing energy consumption in conjunction with improving safety standards is an essential target in modern mobility concepts. Hence, the development of strong, tough and ductile steels for

automotive applications is an essential topic in steel research. In this context TWIP (twinning induced plasticity) steels with up to 30 wt.% Mn and >0.4 wt.% C content have shown an excellent

combination of ductility and strength. Increasingly, the reduction in mass density of TWIP steels becomes an additional challenge.

Two effects enable such efforts:

The first one is that Mn increases the fcc lattice parameter. The second one is that very high Mn and C alloying stabilizes the austenite, so that it can tolerate Al additions up to about 10 wt.%

without becoming instable, i.e. transforming into bcc-ferrite.

Such an alloy concept sustains many advantages associated with TWIP steels, e.g. mechanical twinning and very high strain hardening; yet, it enables density reductions of up to 18%. Hence, alloys

based on the quartenary system Fe-Mn-Al-C are specifically promising for the design of low density TWIP steels.

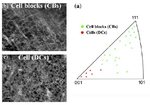

Regarding the excellent mechanical properties of TWIP steels, which are characterized by the transition from dislocation and cell hardening to massive mechanical twinning, it has to be considered

that Al increases the stacking fault energy (SFE). This means that the overall strain hardening behavior and the onset of mechanical twinning in density reduced TWIP grades may differ from those

observed in conventional TWIP steels.

However, alloys based on the Fe-Mn-Al-C system offer an even larger variety in deformation and strain hardening mechanisms than those associated with the TWIP effect alone. This is due to the

characteristic dislocation substructures and the higher number of phases present in the Fe-Mn-Al-C system, namely, fcc-austenite, bcc-ferrite, and ordered structures such as DO3 and L’12-type

carbides. Depending on composition, low density steels can assume austenitic structure for the composition regime Mn: 15-30 wt.%, Al: 2-12 wt.%, and C: 0.5-1.2 wt.%. In order to combine the

advantages of the TWIP mechanisms with the reduction in specific weight this alloy range is hence the most promising one. When increasing Al content to a range >6-8.wt%, strain hardening in these

steels is less dominated by the TWIP effect but instead by the formation of nano-sized L’12-type carbides, so-called κ-carbides.

Density reduced steels with ferritic structure have compositions in the range Mn <8 wt.%, Al: 5-8 wt.%, and C <0.3 wt.%. Corresponding complex grades, consisting of austenite and ferrite can be

synthesized by using compositions Mn: 5-30 wt.%, Al: 3-10 wt.%, and C: 0.1-0.7 wt.%. Besides these compositions, ordered D03 structures, i.e. near-ferritic Fe-Al-Cr alloys without Mn have also been

addressed in the past in the context of density reduced alloy design.

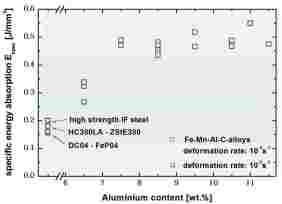

When comparing the synthesis and properties among the different classes of weight reduced steels, alloys based on the austenitic Fe-Mn-Al-C system are most attractive due to their superior strain

hardening, high energy absorption, high density reduction and robust response to minor changes in composition and processing. Even thin strip casting with associated in-line hot rolling has been

successfully conducted in our group as a pathway for efficient small-scale manufacturing of such grades.

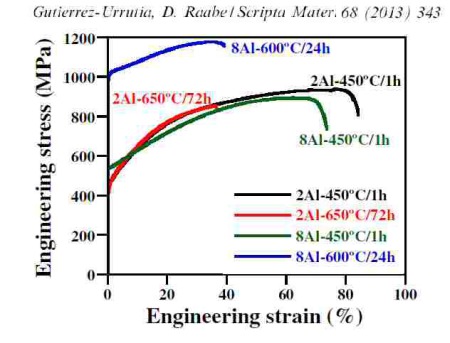

Recent publications on austenitic Fe-Mn-Al-C alloys have reported yield strength values of 0.5-1.0 GPa, elongations to fracture in the range 30–80%, and ultimate tensile strength in the range of

1.0–1.5 GPa.

When blended with an Al content below 5 wt.% a single austenite phase prevails at room temperature, showing excellent strain hardening which was attributed to the hierarchical evolution of the

deformation substructure. Al also promotes formation of nano-precipitates upon aging with L’12 structure and approximate stochiometry of (Fe, Mn)3AlC. These phases are referred to as κ-carbides. They

belong to the group of non-oxide perovskites. Due to their ordered fcc structure, κ-carbides have a lattice mismatch below 3% with respect to an austenitic Fe-Mn-C matrix phase and can hence form

cuboidal nano-precipitates. When embedded in a ferritic matrix the lattice mismatch can be as large as ~6% which leads to semi-coherent interfaces and, hence, different precipitate

morphologies.

This webpage provides a concise introduction to some recent developments in the field of low density Fe-Mn-Al-C TWIP steels placing attention on alloy design, synthesis routes, and

microstructure-property relations. We also provide a brief outlook on pending questions associated with the role of κ-carbides on strain hardening and hydrogen embrittlement.

Here we introduce a new approach to the compositional and thermo-mechanical design and rapid maturation of bulk structural weight reduced steels. This method, termed rapid alloy prototyping (RAP), is based on semi-continuous high throughput bulk casting, rolling, heat treatment and sample preparation techniques.

Acta-Mater-2012-RAP--30Mn-triplex-steels[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.3 MB]

Hydrogen embrittlement of a precipitation-hardened Fe-26Mn-11Al-1.2C (wt.%) austenitic steel was examined by tensile testing under hydrogen charging and thermal desorption analysis. While the high strength of the alloy (>1 GPa) was not affected, hydrogen charging reduced the engineering tensile elongation from 44 to only 5%.

2014 Int J Hydrogen Energy Hydrogen embr[...]

PDF-Dokument [4.1 MB]

We investigate the kinetics of the deformation structure evolution and its contribution to the strain hardening of a Fe–30.5Mn–2.1Al–1.2C (wt.%) steel during tensile deformation by means of transmission electron microscopy and electron channeling contrast imaging combined with electron backscatter diffraction.

2012-Acta FeMnAlC-multi-strain-hardening[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.8 MB]

Scripta-Mater-68 (2013) 343–weight-reduc[...]

PDF-Dokument [721.1 KB]

Here we introduce the alloy design concepts of high performance austenitic FeMnAlC steels, namely,Simplex and alloys strengthened by nanoscale ordered kappa-carbides. Simplex steels are characterised by an outstanding strain hardening capacity at room temperature.

Mater Sc Techn 2014 VOL 30 1099 weight r[...]

PDF-Dokument [390.1 KB]

What is Metastability Alloy Design and Segregation Engineering and how is it done ?

some remarks on metastable bulk metallic[...]

PDF-Dokument [3.7 MB]