Sustainable Metals and Green Metallurgy

What is Sustainable Metallurgy and why is it important ?

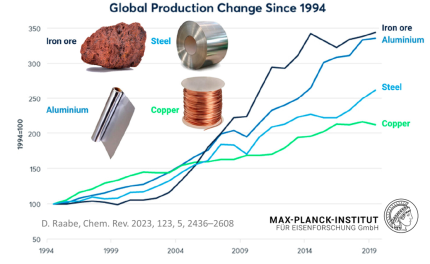

Metallic materials such as steels, aluminium, titanium, lithium or nickel which have enabled progress over thousands of years and given entire ages their name, are now facing severe limits set by sustainability. The accelerated demand for practically all structural alloys in key areas such as energy, infrastructure, medicine, safety, construction and transportation creates huge growth rates of up to 200% until 2050. Yet, most of these metallic materials are energy, greenhouse gas and pollution intense when extracted and manufactured.

Brief Introduction ot the topic on youtube:

Sustainable Metallurgy and Green Metals - A Green Metallurgy Introduction

Video about sustainable metallurgy and green metals

In a set of projects we study approaches to improve the sustainability of and through structural metallic alloys. We work on ideas related to progress in direct sustainability for different steps along the value chain including CO2-reduced primary synthesis; recycling; scrap-compatible alloy design, contaminant tolerance of alloys, and improved alloy longevity through corrosion protection, damage tolerance and repairability for longer product use. We also investigate how structural materials enable improved energy efficiency through reduced weight, higher thermal stability, and better mechanical properties. The respective leverage effects of the individual measures on rendering structural alloys more sustainable can be quantified.

What is the role of steels in sustainable metallurgy?

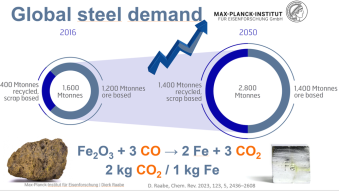

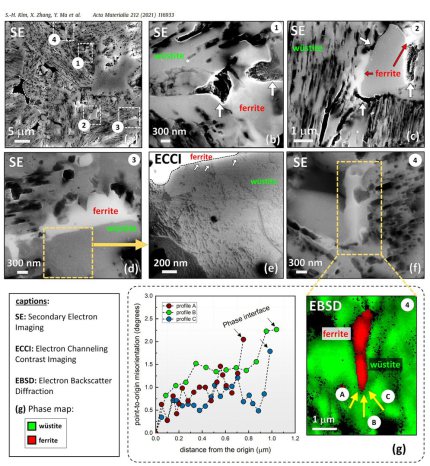

Steel is the most important material class in terms of volume and environmental impact. While it is a sustainability enabler, for instance through lightweight design, magnetic devices, and efficient turbines, its primary production is not. Iron is reduced from ores by carbon, causing 30% of the global CO2 emissions in manufacturing, qualifying it as the largest single industrial greenhouse gas emission source. Hydrogen is thus attractive as alternative reductant. Although this reaction has been studied for decades, its kinetics is not well understood, particularly during the wüstite reduction step which is much slower than hematite reduction.

Hence, steel plays an eminent role in sustainable metallurgy due to its versatility, durability and recyclability.

- Versatility: Steel can be used in a wide range of applications, from construction to transportation, infrastructure, energy production, and consumer goods. This versatility means that it can be used in a variety of sustainable projects such as wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles.

- Durability: Steel is a very durable material, which means that it can last for many years and in part even a full century without needing to be replaced. This makes it a good material for sustainable construction projects, as it reduces the need for constant maintenance and replacement.

- Recyclability: Steel is a highly recyclable material, and can be recycled indefinitely without losing any of its properties. At global average around 30-40% of the steel produced today is made from recycled steel. This helps to conserve natural resources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Iron and steel making can have significant impacts on soil, water, and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Soil: During the process of mining iron ore, soil may be disturbed, and erosion can occur, leading to soil degradation. Additionally, the disposal of waste products from the mining process can result in the contamination of soil with heavy metals and other pollutants.

- Water: Water usage is high in the iron and steel making process, with large amounts of water required for cooling and processing. This can lead to the depletion of local water resources and can also result in water pollution if contaminants from the process are discharged into rivers, lakes, or oceans.

- Greenhouse gas emissions: Iron and steel making is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, with the production of iron and steel accounting for approximately 7% of global carbon dioxide emissions. These emissions are primarily due to the use of coal and other fossil fuels in the process, which release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

There are a number of metallurgical and engineering challenges associated with the recycling of steel:

- Contamination: Steel scrap can be contaminated with several types of harmful elements such as zinc, tin, copper, lead, aluminum, etc., which all can substantially affect the quality of the recycled steel. Developing scrap sorting and metallurgical processing methods for effectively separating and removing these contaminants is an essential scientific challenge, particularly when aiming at the production of safety-critical and high performance steels.

- Alloying elements: Steel alloys contain different types and levels of expensive and critical alloying elements, which affect the properties of the steel. Recycling and reusing these elements for new alloys requires a thorough understanding of the chemistry of the steel and the alloying elements. Examples are Titanium, Niobium, Vanadium, Chromium, Nickel, Manganese, etc.

- Energy consumption: Steel recycling requires significant amounts of energy, particularly during the melting process (e.g. in electric arc furnaces). Finding ways to reduce the energy consumption and carbon footprint of the recycling process is a scientific challenge. Also, priority should be placed on melting steel scrap with sustainable electricity and renewable fuel.

- Material properties: Recycled steel may have different material properties than virgin steel due to differences in composition and processing. Developing methods for accurately characterizing and predicting the properties of recycled steel is a huge scientific challenge.

- Corrosion resistance: Recycled steel may have reduced corrosion resistance due to the presence of impurities, intermetallics, undesired carbides, segragtion, and contaminants. Developing methods for improving the corrosion resistance of recycled steel is therefore essential.

- Recycling of complex products: Steel is used in a wide range of products, including automobiles, appliances, and construction materials, many of which are complex and difficult to recycle. Developing methods for efficiently and effectively recycling these complex products is a scientific challenge.

Main direction in metallurgical sustainability research

- More sustainability in production and processing: To reduce CO2 emissions in the primary production of metals, the share of scrap that can be recycled must be increased.

- Sorting and recycling: To increase the share of recycled metal, scrap needs to be better sorted. To do this, recyclers need new techniques to identify, separate, clean and crush alloys.

- Recycling-friendly alloy design: Until now, alloys have mostly been optimised for single use, but in the future, the design of composition and properties will have to take recyclability more and more into account, to match the need for a circular economy

- Durability of alloys through corrosion protection and multiple use: The ecological footprint of the metal industry can also be reduced by making alloys or the components made from them more durable. This includes corrosion research and improved resistance of alloys to hydrogen embrittlement.

- Energy efficiency through lightweight construction and temperature resistance: In many cases, according to the materials scientists in Nature, the efficiency of the application can already be improved through the design of the components.

Main routes for steel production and their impact on the environment - why do we need green steel ?

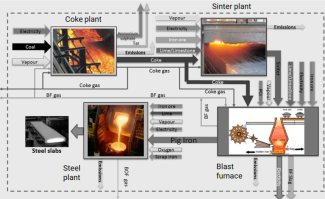

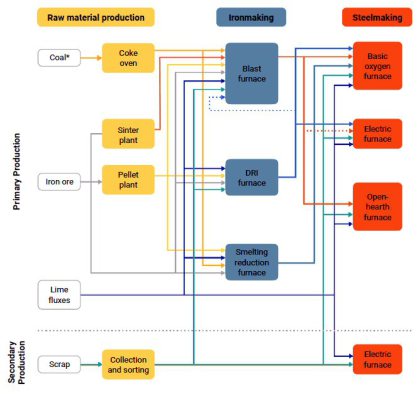

Iron and steel are today mainly produced via two main routes: the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route and electric arc furnace (EAF) route.

The difference between them is the types of raw materials in terms of ores and reductant feedstock they consume.

For the BF-BOF route these are predominantly iron ore, coal, and a small fraction of recycled steel (for cooling the steels in the BOF operation), while the EAF route produces steel using mainly scraped and recycled steel grades and electricity (here it is bvery important which carbon-footprint the electricity carries).

Depending on the specific iron and steel plant plant configuration and availability of recycled steel,

other sources of metallic iron such as direct-reduced iron

(DRI) or hot metal can also be used in the EAF route.

About 70% of steel is globally produced through the BF-BOF processing route. First, iron ores are reduced to iron, also called hot metal or pig iron. Then the iron is converted to steel in

the BOF.

The fact that carbon carriers serve as reducing agents in the blast furnace operation is the main cause for the high CO2 emissions associated with iron making. Our reserach adresses these challenges.

PDF-Dokument [10.2 MB]

Is direct reduction a viable method for steel making?

Direct reduction is a process for producing iron from iron oxides. The process involves the solid state reduction of the iron oxide below the melting point of iron with a reducing gas (such as hydrogen, methane, syngas or carbon monoxide) at high temperatures, typically in the range of 800-1200°C.

In the context of steelmaking, direct reduction is used to produce iron that is then further processed and alloyed via ladle metallurgy to make steel.

Interestingly direct reduction was the most prevalent form of iron production throughout Europe and the Middle East until the 16th century. The introduction of the blast furnace helped revolutionize the iron manufacturing process and soon became the standard for production. As demand for iron increased, the blast furnace made it possible to produce large amounts of iron in a relatively short period of time. The type of iron made by blast furnaces, however, is not direct-reduced iron but pig iron, which isn't as rich as direct reduced iron.

The direct reduction process has a few advantages over traditional blast furnace plus oxygen converter methods of producing iron, including lower capital costs, reduced energy consumption, and (much) lower carbon emissions (particularly when using hydrogen as reductant).

The direct reduction of iron oxides can be carried out using several different technologies, including fluidized bed reactors, and shaft furnaces. The choice of technology depends on a range of factors, including the quality and dispersion of the iron ores, the desired product specifications, and the local infrastructure and energy costs.

In general, the direct reduction process involves the following steps:

Pre-treatment: The iron ore is first crushed and screened to remove any impurities and prepare it for reduction.

Reduction: The iron oxide is then reduced to metallic iron by a reducing gas, recently by using hydrogen or - more commonly - by using methane. The reduction reaction by using hydrogen can be represented by the following equation:

Fe2O3 + 3H2 → 2Fe + 3H2O

Cooling and separation: The reduced iron is then cooled and separated from the gas stream. The resulting iron is typically in the form of direct-reduced iron (DRI) or hot briquetted iron (HBI).

Further processing: The DRI or HBI is then further processed to make steel using a variety of methods, including electric arc furnaces, basic oxygen furnaces, and other secondary refining processes.

Overall, the direct reduction process is an important part of modern steelmaking, offering a more efficient and sustainable alternative to traditional blast furnace methods of producing iron.

There are a few drawbacks to direct reduction. The manufacturing procedure requires unusually large quantities of natural gases (or hydrogen, syngas etc), which limits the areas of the world in which it can be produced.

Another drawback to direct reduced iron is its sensitivity to oxidation and rusting. It needs to be stored and used in temperature-appropriate conditions to ensure its longevity. Direct reduced iron in large amounts has also been known to spontaneously burst into flames when exposed to open air.

What are the typical raw and feedstock materials for iron and steel making?

Due to the different steel production methods in use today different types of raw materials are used.

Crude steel is predominantly produced via a basic oxygen furnace (BOF), at a smaller extend in an electric arc furnace (EAF), and very rarely, in an open hearth furnace (OHF). EAFs can be fed scrap metal, pig iron from blast furnaces or iron sponge from direct reduction (DRI) processes, or hot briquetted iron, or some combination of these iron sources.

Blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) steelmaking uses coal as the main fuel source, which not only provides heat but also chemical properties that make

it challenging to replace coal with alternative reduction means, and relegates the main decarbonization option to capturing carbon emissions and storing them underground, known as carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS).

BOFs and OHFs are typically fed pig iron, but may be supplemented with smaller amounts of scrap metal or DRI. Pig iron is typically produced from iron ore and coking coal (coke) in a blast furnace (BF) and DRI is produced in a direct reduced iron plant from iron ore (without any coking coal) and a reduction gas, mostly methane, in future probably also hydrogen. Some steel plants operate only one type of production route (typically either BF-BOF or DRI-EAF), but some operate multiple different production routes.

What is the role of microstructure for the hydrogen-based reduction of iron ores?

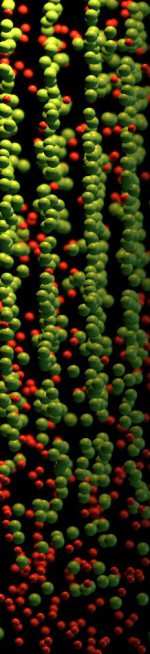

Hydrogen is an attractive candidate as alternative reductant, replacing carbon. Although the hydrogen-based reduction of iron oxides has been studied for decades, its kinetics is not well understood, particularly during the wüstite reduction step which is much slower than hematite reduction. Some rate-limiting factors of this reaction are determined by the microstructure and local chemistry of the ores. Here, we report on a multi-scale structure and composition analysis of iron reduced from hematite with pure H2, reaching down to near-atomic scale. During reduction a complex pore- and microstructure evolves, due to oxygen loss and non-volume conserving phase transformations. The microstructure after reduction is an aggregate of nearly pure iron crystals, containing inherited and acquired pores and cracks. We observe several types of lattice defects that accelerate mass transport as well as several chemical impurities (Na, Mg, Ti, V) within the Fe in the form of oxide islands that were not reduced. With this study, we aim to open the perspective in the field of carbon-neutral iron production from macroscopic processing towards better understanding of the underlying microscopic transport and reduction mechanisms and kinetics.

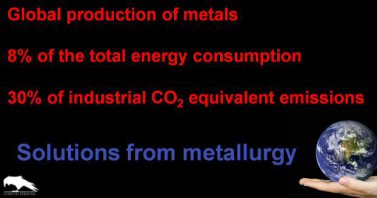

What is the motivation for research on Sustainable Metallurgy?

What is the motivation for research on Sustainable Metallurgy?

To answer this question, we must realise the huge environmental impact of metallurgy!

The global production of metals and metallurgical products stands for the gigantic number of about 8% of the total energy consumption on the planet.

It is also responsible for 30% of all industrial CO2 equivalent emissions.

These contribute as greenhouse gas enormously to global warming.

Therefore, we work on solutions that metallurgy can provide in that context.

What are conserved and what are non-conserved quantities in metallurgy?

It is quite interesting to note that, while mass and energy are conserved quantities, which motivate us to develop elements of a circular economy, the microstructures of materials, which

actually determine most of the properties of materials, particularly of load bearing materials, are not conserved quantities.

This simple but interesting aspect brings the question up, whether microstructures can be actually rejuvenated by adequate processing, rather than scrapping the part that is taken out of

service.

Alternatively one could even think about the rejuvenation of microstructures and the associated properties when a part is still in service.

What is direct and indirect sustainability in metallurgy?

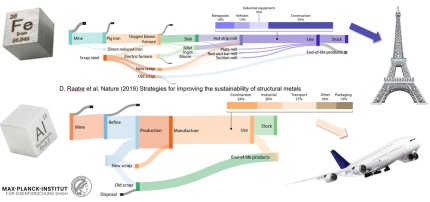

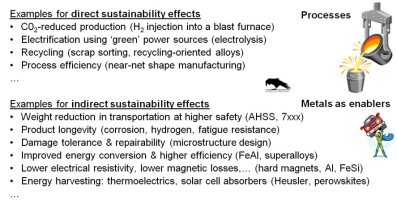

There are direct and indirect measures to improve the sustainability of metals and through the use of metals. Direct sustainability effects refer to implementing more sustainable production and manufacturing methods along the value chain including CO2-reduced primary production, higher fractions of secondary production through recycling and more efficient manufacturing. In this context one can also think about opportunities to render alloy-design upfront more recycling-oriented.

Indirectly sustainability in metallurgy refers to sustainability that is enabled through the use of metals, e.g. through improved energy conversion in turbines and related machine and weight reduction in transportation at maintained or even higher safety and lower costs. Also, materials for lower tribology and abrasion losses belong in this category. Another strategy focuses on improved alloy longevity through corrosion protection, damage tolerance and repairability for longer product use.

Some examples for direct and indirect sustainability effects in metallurgy

Let me give you some examples for both, direct, and indirect sustainability effects.

Direct sustainability effects refer to the reduction of emissions and energy consumption during the synthesis and manufacturing of metals.

In that context, the reduction in the CO2 emissions, stemming from metallurgical processes, deserves highest attention.

A typical example is the current attempt, to inject hydrogen gas into blast furnaces. The aim is to use hydrogen as reductant, so as to reduce the fraction of iron ore reduced by carbon.

A future alternative is to operate so called direct reduction furnaces entirely with hydrogen, instead of methane gas.

A second direction is the electrification of the metallurgical manufacturing chain, including for instance, advanced electrolysis solutions.

Next is the recycling of metallic scraps, and remelting them into fresh material. This requires research on advanced scrap sorting technologies, and in the future also on recycling-oriented alloy

design.

Recycling-friendly alloys should be characterised for example by a high tolerance against undesired impurity elements, that can enter through the scraps.

Another aspect concerns the overall process efficiency. An example is near-net-shape manufacturing, such as known for instance from thin slab or thin strip casting.

Next are some examples for indirect sustainability effects in metallurgy.

These refer to the reduction of emissions and energy consumption, that are enabled, when using advanced materials, for making other products, processes, or services, more sustainable.

A well-known example is weight reduction in the transportation sector.

This is achieved by high-strength alloys, such as high strength steels or 7000 series aluminum alloys.

Of highest relevance is the increase in product longevity, achieved through improved corrosion, hydrogen, and fatigue resistance of materials and coatings.

The same applies for advanced microstructure design opportunities.

These can be realised, through damage-tolerant and even repairable microstructures.

Another important field, is the improvement of the efficiency of machines, that are used for energy conversion, such as turbines.

This can be aided through the use of advanced high temperature, corrosion, and creep resistant materials.

Examples are weight-reduced super-alloys or Iron-aluminide composites.

Better sustainability can be also realized when using electrical conductors with lower resistance, or magnetic materials with lower magnetic hysteresis losses, for the case of soft magnets, or higher

remanence, for the case of hard magnets.

These functional properties of alloys play a huge role for the electrification of industry with green energy sources.

An essential contribution is made by materials, that can serve for energy harvesting. Examples are thermoelectric materials and solar-cell absorbers.

Why are metals of special interest in the context of sustainability ?

Metallic alloys ply a key role of historic and enduring importance for industry and society. They have paved the path of human civilization with load-bearing applications that can be used under the harshest environmental conditions, witnessed by whole ages that carry their names. Only metallic materials encompass such diverse features as strength, hardness, workability, damage tolerance, joinability, ductility and toughness, often furnished with additional functional properties such as corrosion resistance, thermal and electric conductivity and magnetism.

This versatility in property combinations comes together with a vast understanding of thermo-mechanical processing of metals (build-up over millennia of metals use), which in turn enable numerous production, manufacturing, design, repair, and recycling pathways.

Because of these property advantages, metals have been key-enablers for multiple applications in the fields of energy conversion, transportation, construction, communication, health, safety, and infrastructure. Examples over the ages have been agricultural tools, manufacturing machinery, energy conversion engines and reinforcements in huge concrete-based infrastructures. Recent applications include structural alloys for weight reduction combined with high strength and toughness in the transportation sector, efficient turbines operating at higher temperatures for power plants and air traffic, components for safe nuclear and fusion power and disposal, targeted endurance or corrosive dissolution of biomedical implants8, embrittlement resistant infrastructures for hydrogen-based industries9 or reusable spacecraft to name a few. This success story has turned metallurgical alloys and products into a key innovation and economy booster: the global market for metals is about 3000 billion € per year.

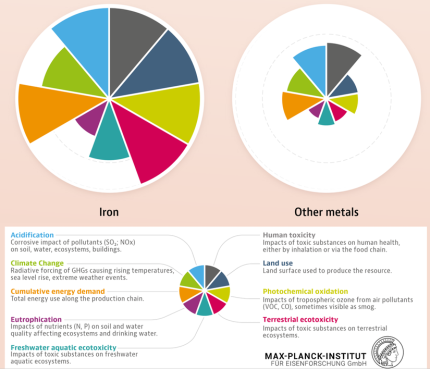

What is the environmental impact of metals and their production?

The great success of metallic materials and the associated industries also means that they have an important role to play in addressing the current environmental challenges. The availability of metals (most of the elements used in structural alloys are among the most abundant), efficient mass producibility, low price and amenability to large scale industrial production (extraction and beneficiation up to the metal alloy) and manufacturing (downstream operations after solidification) have become a significant environmental burden:

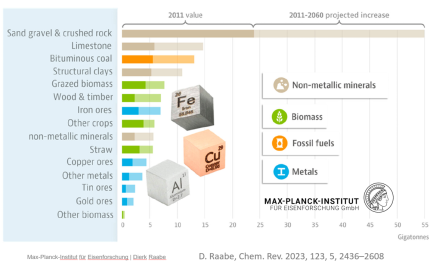

The sheer magnitude of the worldwide production of metals leads to a total energy consumption of about 53 Exa-Joule (1018 Joule) (8% of the global energy) and almost 30% of industrial CO2 equivalent emissions (4.4 Gt CO2eq) when only counting steels and aluminum alloys (the largest fraction of metal use by volume). While the production volumes of nickel and titanium are much smaller, their impact is worthy of remark because of the eminent role they play for aerospace and biomedical materials, and the strong link to stainless steel for the case of nickel (stainless steel accounts for two-thirds of nickel’s uses). The worldwide annual production in terms of mass, energy and CO2 is presented here, with metal lost in manufacturing for these four key structural metals (where Ni use in stainless steel is the focus).

Mining and production of these materials has a staggering impact in terms of resource use, emissions, and waste generation, and this impact continues to grow, because of trends around

urbanization, electrification, and digitization (in 1950 less than 30% of the population lived in cities this number is projected to exceed 60% by 2025). In addition, there are significant byproducts

of both industries that cause significant environmental damage when not managed properly in perpetuity (losses throughout the supply chain are shown here along with the quantities of material recovered as scrap). The two largest material groups alone create huge mining and

extraction byproducts, namely, 2,400 million tons/yr tailings and 220 million ton/yr slags for the case of steels and 160 million ton/yr bauxite residue for the case of Al.

Recent examples, such as an iron-ore mining dam collapse in the mineral-rich state of Minas Gerais, Brazil in 2019 or the Ajka spill in 2010 where 100 thousand m3 of red mud breached a dam, show that

these byproducts provide a constant threat and risk associated with extraction of the precursors to structural alloys.

These significant energy consumption challenges and detrimental environmental impacts are the biggest obstacle for further use of structural metals (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 in the original paper).

The role of steels for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions

The primary synthesis of steel poses the biggest challenge when aiming at reducing greenhouse gas emssions owing to the huge quantities produced each year (1.8 billion tons per year) and the use of carbon carriers as reductants (since about 3500 years).

In the production of iron (which is the precursor of steel) via the conventional process route based on the use of iron ore - i.e. via a blast furnace in which the iron ore is melted into pig iron and a steel converter in which the pig iron is subsequently further purified - greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2), are produced in huge quantities.

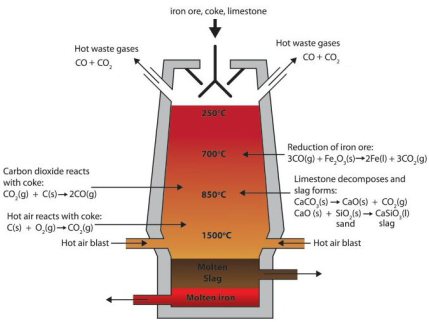

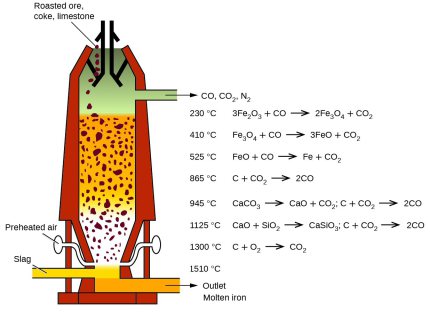

What is the role of the blast furnace process on greenhouse gas emissions ?

When producing iron via the blast furnace process route around 1.7 tons of CO2 emissions are produced per ton of crude steel. Most of the CO2 is generated in a chemical process that takes place in the blast furnace.

The oxygen in the iron ore has to be split off. Today, coke produced from coal in coking plants is usually used for this purpose. It is heated with hot air in the lower part of the blast furnace and gasified with the oxygen content of the air to form the reducing gas carbon monoxide.

This means that the main chemical reaction producing the molten iron is Fe2O3 + 3CO → 2Fe + 3CO. This reaction is actually subdivided into a chain of multiple steps, with the first one being that preheated blast air blown into the furnace reacts with the carbon in the form of coke to produce carbon monoxide and heat: 2 C(s) + O2(g) → 2 CO.

The gas rises to the top and binds the oxygen contained in the iron ore, converting it to carbon dioxide (CO2). The liquid pig iron is then converted to crude steel in a converter by blowing in oxygen to remove other interfering components such as carbon, silicon, phosphorus or sulphur particles.

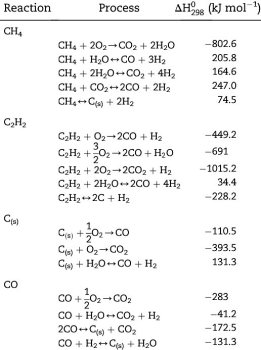

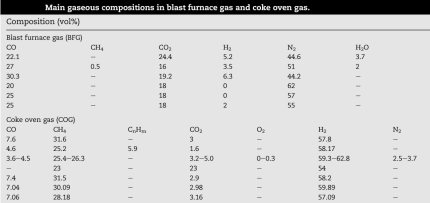

An imprtant factor is the composition of the coke gas that is feed into the blast furnace:

Coke oven gas is formed by heating coal to 1100 °C without access of air. The classic composition of coke gas: hydrogen (H2 - 51%), methane (CH4 - 34%), carbon monoxide (CO - 10%), ethylene (C2H4 - 5%). The composition may also include benzene (C6H6), ammonia (NH3), hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and other components.

Main chemical redox reactions in the blast furnace and how to influence them

In the blast furnace, several chemical processes take place simultaneously, in which the ore is reduced to iron over several stages and the non-reducible fractions are transferred into the slag.

In order to initiate a reduction of the ore in the first place, however, the reducing gases must at first be generated. This is done in the lower part of the furnace during the combustion of the carbon contained in the coke with oxygen.

The reaction C+O2 -> CO2 is strongly exothermic (394.4 kJ/mol) and heats the blast furnace in the area of the hot blast ring nozzles to a temperature of 1800 to 2000 °C, with the use of additional oxygen even to 2200 °C.

However, two endothermic, i.e. heat-consuming, reactions immediately following this lower the temperature again to about 1600 to 1800 °C.

The Boudouard reaction CO2+C -> 2CO which however requires a minimum temperature of 1000 °C, requires 172.45 kJ/mol.

A simultaneous splitting of the water vapor in the hot gas H2O+C - > H2+CO needs another 131.4 kJ/mol.

The two reducible gases carbon monoxide and hydrogen rise upwards against the material flow in the blast furnace.

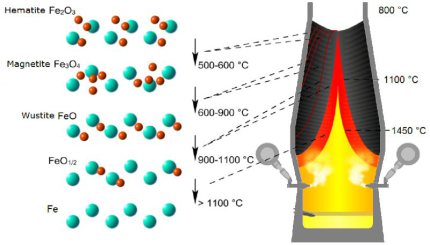

In the temperature zone between 400 and 900 °C the so-called "indirect reduction" takes place. Over three stages, the various iron oxides react with carbon monoxide or hydrogen, respectively, until finally metallic iron is obtained.

What is the balance among the carbon monoxide and hydrogen reduction processes in the blast furnace ?

As long as the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced remains in the temperature range of over 1000 °C, it is repeatedly regenerated to carbon monoxide (CO) by the Boudouard reaction and is available again for the reduction process.

The competing iron ore reduction by hydrogen is particularly effective at around 800 °C.

A content of only 10 % hydrogen in the reaction gas triples the rate of reduction, but the rate of reduction decreases again as the temperature increases further. Also, the grain size of the ore must not exceed a certain level so that the diffusion paths of the hydrogen do not become too large.

What is electronic scrap and how is it recycled?

Electronic waste or electrical and electronic equipment or components thereof which are no longer used because they either no longer fulfil their intended purpose or have been replaced by better equipment. Electronic scrap can be classified into different categories.

According to a UN report, approximately 50 million tons of electronic waste are generated worldwide every year, of which only 20% is recycled in an orderly manner.

What are the gains and risks when recycling electronic scrap?

On the one hand, electronic scrap consists of valuable materials that can be recovered as secondary raw materials. On the other hand, it contains a variety of heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, cadmium and mercury, halogen compounds such as polybrominated biphenyls, PVC, chlorinated, brominated and mixed halogenated dioxins and other highly toxic and environmentally hazardous substances. Dioxins are carcinogenic, fruit-damaging, very persistent and accumulate in fatty foods (meat, milk, etc.) (bioaccumulation). The use and placing on the market of components containing PCBs has been prohibited in the EU since the 1980s (PCB Prohibition Ordinance), which means that they are no longer present to any significant extent in today's electrical and electronic waste.

Mobile phone scrap plays a particular role: Electronic devices have a shorter product life cycle than before; their number has increased significantly worldwide. Germany's 38 million households produced an estimated 1.1 million tons of electronic scrap in 2005.

The recycling rates of electronic waste is very small, often not exceeding 20%. Some industrialised countries, including the USA, European countries and Australia, prefer to export their electronic waste to emerging and developing countries. It is estimated that 50 to 80% of electronic waste is exported from industrialized countries. There, substances are removed from the electronic waste by the simplest means (fire, hammer and pliers, acid bath, etc.) and with great harm to people and the environment. In addition to adults, children often also carry out this recycling. To prevent the cross-border transport of hazardous waste, many countries signed the Basel Convention.