Aluminium Alloys

Some basic features of Aluminium and its alloys

Aluminium is the third most plentiful element known to man, only oxygen and silicon exist in greater quantities. The element aluminium, chemical symbol Al, has the atomic number 13.

Lightness is an essential property of aluminium. The metal has an atomic weight of 26.98 and a specific gravity of 2.70, approximately one-third the weight of

other commonly used metals; with the exception of titanium and magnesium.

The electrical conductivity of 99.99% pure aluminium at 20°C is 63.8% of the

International Annealed Copper Standard (IACS). Because of its low mass density, the mass electrical conductivity of pure aluminium is more than twice that of annealed copper and greater

than that of any other metal. The resistivity at 20°C is 2.69 uOhm cm. The electrical conductivity which is the reciprocal of

resistivity, is one of the more sensitive properties of aluminium being affected by both, changes in composition and thermal treatment. The addition of other metals in aluminium alloys

lowers the electrical conductivity of the aluminium therefore this must be offset against any additional benefits which may be gained, such as an increase in strength. Heat treatment also

affects the conductivity since elements in solid solution produce greater resistance than undissolved constituents.

The thermal conductivity, κ, of 99.99% pure aluminium is 244 W/mK for the temperature range 0-1ß0°C which is 61.9% of the IACS, and again because of its low mass density its mass thermal conductivity is twice that of copper.

When exposed to air, a layer of aluminum oxide forms almost instantaneously on the surface of the aluminum. This layer has excellent resistance to corrosion. It is fairly resistant to most acids but less resistant to alkalis. Hence, aluminium has a higher resistance to corrosion than most other construction metals owing to the protection conferred by the thin but tenacious and very dense oxide film. This oxide layer is always present on the surface of aluminium in oxygen atmospheres.

Historical facts about Aluminium and its alloys

Aluminium was first isolated by Oersted 1825 and produced chemically as small ingots by Sainte-Claire Deville in France in 1855. At that time, aluminium was more expensive than gold but attracted the attention of Napoleon III who foresaw its use for military purposes such as lightweight body armour. Following the availability of high voltage supplies of electricity, independent discoveries by Hall and Heroult in 1886 led to the development of an economic method for extracting aluminium that remains the metals's production method today.

Discovery of the age hardening effect in Aluminium alloys

Even after several years of intense research Aluminium remained too soft for many applications. This changed in 1906, when a German metallurgist, Alfred Wilm, was studying the effects of copper and other doping elements to aluminium in the quest of identifying a stronger and lighter replacement material for brass in cartridge cases.

One of these alloy variants, Al-3.5%Cu-0.5%Mg, was heated and quenched into water to see if it would harden like steel given a similar treatment. Initial results that he observed at the end of a working week were disappointing but, to his great surprise, tests made by chance after the weekend when he returned to the lab revealed that the alloy had become significantly harder and stronger. The phenomenon was called “age hardening” and it represented the only new method of hardening alloys by heat treatment since the effects of quenching of steel were discovered in the second millennium BC In 1909, Wilm gave to the Dürener Metallwerke (situated between Düsseldorf and Aachen) in Düren sole rights to his patents and this firm produced the first sheet in the famous composition known as “Duralumin”. This alloy was quickly adopted in 1911 for structural members of the Zeppelin airships and then for the first all metal aircraft, the Junkers F 13, that first flew in 1919. Age hardened aluminium alloys have continued to be the principal materials for aircraft construction which, in turn, has provided continuing stimulus for new alloy development.

Solubility and associated effects of elements in aluminium

Mg, Cu, Ag, Zn and Si are alloying elements in aluminium, which have high solid solubility in the Al matrix.

In contrast, Cr, Mn and Zr are mainly used to form compounds to control grain structure.

Details on specific alloying elements:

Antimony occurs in trace amounts (0.01 to 0.1 ppm) primary in commercial aluminum. Antimony has very small solid solubility in aluminum (<0.01%). Some bearing alloys contain up to 4 to 6% Sb. Antimony can be used instead of bismuth to counteract hot cracking in aluminum-magnesium alloys.

Beryllium occurs in aluminum alloys containing magnesium to reduce oxidation at elevated temperatures. Up to 0.1% Be is used in aluminizing baths for steel to improve adhesion of the aluminum film and restrict the formation of the deleterious iron-aluminum complex.

Bismuth. The low-melting-point metals such as bismuth, lead, tin, and cadmium are added to aluminum to make free-machining alloys. These elements have a restricted solubility in solid aluminum and form a soft, low-melting phase that promotes chip breaking and helps to lubricate the cutting tool. An advantage of bismuth is that its expansion on solidification compensates for the shrinkage of lead. A 1-to-1 lead-bismuth ratio is used in the aluminum-copper alloy, 2011, and in the aluminum-Mg-Si alloy, 6262. Small additions of bismuth (20 to 200 ppm) can be added to aluminum-magnesium alloys to counteract the detrimental effect of sodium on hot cracking.

Boron is used as alloying element in aluminum and its alloys as a grain refining agent and for improving conductivity by precipitating vanadium, titanium, chromium, and molybdenum. Boron can be used alone (at levels of 0.005 to 0.1%) as a grain refiner during solidification, but becomes more effective when used with an excess of titanium. Commercial grain refiners commonly contain titanium and boron in a 5-to-l ratio.

Cadmium is a relatively low-melting element that finds limited use in aluminum. Up to 0.3% Cd may be added to aluminum-copper alloys to accelerate the rate of age hardening, increase strength, and increase corrosion resistance. At levels of 0.005 to 0.5%, it has been used to reduce the time of aging of aluminum-zinc-magnesium alloys.

Calcium has very low solubility in aluminum and forms the intermetallic CaAl4. An interesting group of alloys containing about 5% Ca and 5% Zn have superplastic properties. Calcium combines with silicon to form CaSi2, which is almost insoluble in aluminum and therefore will increase the conductivity of commercial-grade metal slightly. In aluminum-magnesium-silicon alloys, calcium will decrease age hardening. Its effect on aluminum-silicon alloys is to increase strength and decrease elongation, but it does not make these alloys heat treatable.

Carbon occurs in aluminium as an impurity element as oxycarbides and carbides, of which the most common is A14C3, but carbide formation with other impurities such as titanium is possible. A14C3 decomposes in the presence of water and water vapor, and this may lead to surface pitting.

Cerium, mostly in the form of mischmetal (rare earths with 50 to 60% Ce), has been added experimentally to casting alloys to increase fluidity and reduce die sticking.

Chromium occurs as a minor impurity in commercial-purity aluminum (5 to 50 ppm). It has a large effect on electrical resistivity. Chromium is a common addition to many alloys of the aluminum-magnesium, aluminum-magnesium-silicon, and aluminum-magnesium-zinc groups, in which it is added in amounts generally not exceeding 0.35%. In excess of these limits, it tends to form very coarse constituents with other impurities or additions such as manganese, iron, and titanium. Chromium has a slow diffusion rate and forms fine dispersed phases in wrought products. These dispersed phases inhibit nucleation and grain growth. Chromium is used to control grain structure, to prevent grain growth in aluminum-magnesium alloys, and to prevent recrystallization in aluminum-magnesium-silicon or aluminum-magnesium-zinc alloys during hot working or heat treatment. Chromium is thus mostly added to aluminum to control grain structure, to prevent grain growth in aluminum-magnesium alloys, and to prevent recrystallization in aluminum-magnesium-silicon or aluminum-magnesium-zinc alloys during heat treatment. Chromium will also reduce stress corrosion susceptibility and improves toughness.

Cobalt is an uncommon addition to aluminum alloys. It has been added to some aluminum-silicon alloys containing iron, where it transforms the acicular ß (aluminum-iron-silicon) into a more rounded aluminum-cobalt-iron phase, thus improving strength and elongation. Aluminum-zinc-magnesium-copper alloys containing 0.2 to 1.9% Co are produced by powder metallurgy.

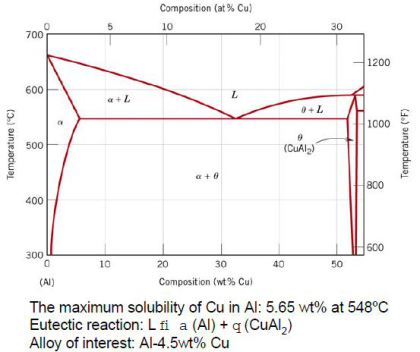

Copper. The aluminum-copper alloys typically contain between 2 to 10% copper, with smaller additions of other elements. The copper provides substantial increases in strength and facilitates precipitation hardening. The introduction of copper to aluminum can also reduce ductility and corrosion resistance. The susceptibility to solidification cracking of aluminum-copper alloys is increased; consequently, some of these alloys can be the most challenging aluminum alloys to weld. These alloys include some of the highest strength heat treatable aluminum alloys. The most common applications for the 2xxx series alloys are aerospace, military vehicles and rocket fins.

Both cast and wrought aluminum-copper alloys respond to solution heat treatment and subsequent aging with an increase in strength and hardness and a decrease in elongation. The strengthening is maximum between 4 and 6% Cu, depending upon the influence of other constituents present.

Copper-magnesium. The main benefit of adding magnesium to aluminum-copper alloys is the increased strength possible following solution heat treatment and quenching. In wrought material of certain alloys of this type, an increase in strength accompanied by high ductility occurs on aging at room temperature. On artificial aging, a further increase in strength, especially in yield strength can be obtained, but at a substantial sacrifice in tensile elongation.

Copper-magnesium plus other elements. The cast aluminum-copper-magnesium alloys containing iron are characterized by dimensional stability and improved bearing characteristics, as well as by high strength and hardness at elevated temperatures. However, in a wrought Al-4%Cu-0.5%Mg alloy, iron in concentrations as low as 0.5% lowers the tensile properties in the heat-treated condition, if the silicon content is less than that required to tie up the iron as the aFeSi constituent.

Gallium is an impurity in aluminum and is usually present at levels of 0.001 to 0.02%. At these levels its effect on mechanical properties is quite small. At the 0.2% level, gallium has been found to affect the corrosion characteristics and the response to etching and brightening of some alloys.

Hydrogen has a higher solubility in the liquid state at the melting point than in the solid at the same temperature. Because of this, gas porosity can form during solidification. Hydrogen is produced by the reduction of water vapor in the atmosphere by aluminum and by the decomposition of hydrocarbons. In addition to causing primary porosity in casting, hydrogen causes secondary porosity, blistering, and high-temperature deterioration (advanced internal gas precipitation) during heat treating. It probably plays a role in grain-boundary decohesion during stress-corrosion cracking. Its level in melts is controlled by fluxing with hydrogen-free gases or by vacuum degassing.

Indium. Small amounts (0.05 to 0.2%) of indium have a marked influence on the age hardening of aluminum-copper alloys, particularly at low copper contents (2 to 3% Cu).

Iron is the most common impurity found in aluminum. It has a high solubility in molten aluminum and is therefore easily dissolved at all molten stages of production. The solubility of iron in the solid state is very low (~0.04%) and therefore, most of the iron present in aluminum over this amount appears as an intermetallic second phase in combination with aluminum and often other elements.

Lead. Normally present only as a trace element in commercial-purity aluminum, lead is added at about the 0.5% level with the same amount as bismuth in some alloys (2011 and 6262) to improve machinability.

Lithium. The addition of lithium to aluminum can substantially increase strength and, Young’s modulus, provide precipitation hardening and decreases density.

The impurity level of lithium is of the order of a few ppm, but at a level of less than 5 ppm it can promote the discoloration (blue corrosion) of aluminum foil under humid conditions. Traces of lithium greatly increase the oxidation rate of molten aluminum and alter the surface characteristics of wrought products.

Magnesium is the major alloying element in the 5xxx series of alloys. Its maximum solid solubility in aluminum is 17.4%, but the magnesium content in current wrought alloys does not exceed 5.5%. The addition of magnesium markedly increases the strength of aluminum without unduly decreasing the ductility. Corrosion resistance and weldability are good.

The addition of magnesium to aluminum increases strength through solid solution strengthening and improves their strain hardening ability. These alloys are the highest strength nonheat-treatable aluminum alloys and are, therefore, used extensively for structural applications. The 5xxx series alloys are produced mainly as sheet and plate and only occasionally as extrusions. The reason for this is that these alloys strain harden quickly and, are, therefore difficult and expensive to extrude. Some common applications for the 5xxx series alloys are truck and train bodies, buildings, armored vehicles, ship and boat building, chemical tankers, pressure vessels and cryogenic tanks.

Magnesium-Manganese. In wrought alloys, this system has high strength in the work-hardened condition, high resistance to corrosion, and good welding characteristics. Increasing amounts of either magnesium or manganese intensify the difficulty of fabrication and increase the tendency toward cracking during hot rolling, particularly if traces of sodium are present.

Magnesium-Silicon. The addition of both, magnesium and silicon to aluminum produces the compound magnesium-silicide (Mg2Si). The formation of this compound provides the 6xxx series their heat-treatability. The 6xxx series alloys are easily and economically extruded and for this reason are most often found in an extensive selection of extruded shapes. These alloys form an important complementary system with the 5xxx series alloy. The 5xxx series alloy used in the form of plate and the 6xxx are often joined to the plate in some extruded form. Some of the common applications for the 6xxx series alloys are handrails, drive shafts, automotive frame sections, bicycle frames, tubular lawn furniture, scaffolding, stiffeners and braces used on trucks, boats and many other structural fabrications. Wrought alloys of the 6xxx group contain up to 1.5% each of magnesium and silicon in the approximate ratio to form Mg2Si, that is, 1.73:1. The maximum solubility of Mg2Si is 1.85%, and this decreases with temperature. Precipitation upon age hardening occurs by formation of Guinier-Preston zones and a very fine precipitate. Both confer an increase in strength to these alloys, though not as great as in the case of the 2xxx or the 7xxx alloys.

Manganese. The addition of manganese to aluminum (3xxx ) increases strength somewhat through solution strengthening and improves strain hardening while not appreciably reducing ductility or corrosion resistance. These are moderate strength nonheat-treatable materials that retain strength at elevated temperatures and are seldom used for major structural applications. The most common applications for the 3xxx series alloys are cooking utensils, radiators, air conditioning condensers, evaporators, heat exchangers and associated piping systems. The element is also a common impurity in primary aluminum, in which its concentration normally ranges from 5 to 50 ppm. It decreases resistivity. Manganese increases strength either in solid solution or as a finely precipitated intermetallic phase. It has no adverse effect on corrosion resistance. Manganese has a very limited solid solubility in aluminum in the presence of normal impurities but remains in solution when chill cast so that most of the manganese added is substantially retained in solution, even in large ingots.

Mercury has been used at the level of 0.05% in sacrificial anodes used to protect steel structures. Other than for this use, mercury in aluminum or in contact with it as a metal or a salt will cause rapid corrosion of most aluminum alloys.

Molybdenum is a very low level (0.1 to 1.0 ppm) impurity in aluminum. It has been used at a concentration of 0.3% as a grain refiner, because the aluminum end of the equilibrium diagram is peritectic, and also as a modifier for the iron constituents, but it is not in current use for these purposes.

Nickel. The solid solubility of nickel in aluminum does not exceed 0.04%. Over this amount, it is present as an insoluble intermetallic, usually in combination with iron. Nickel (up to 2%) increases the strength of high-purity aluminum but reduces ductility. Binary aluminum-nickel alloys are no longer in use but nickel is added to aluminum-copper and to aluminum-silicon alloys to improve hardness and strength at elevated temperatures and to reduce the coefficient of expansion.

Niobium. As with other elements forming a peritectic reaction, niobium would be expected to have a grain refining effect on casting. It has been used for this purpose, but the effect is not marked.

Phosphorus is a minor impurity (1 to 10 ppm) in commercial-grade aluminum. Its solubility in molten aluminum is very low (~0.01% at 660oC) and considerably smaller in the solid.

Silicon. The addition of silicon to aluminum (4xxx) reduces melting temperature and improves fluidity. Silicon alone in aluminum produces a nonheat-treatable alloy; however, in combination with magnesium it produces a precipitation hardening heat-treatable alloy. Consequently, there are both heat-treatable and nonheat-treatable alloys within the 4xxx series. Silicon additions to aluminum are commonly used for the manufacturing of castings. The most common applications for the 4xxx series alloys are filler wires for fusion welding and brazing of aluminum. After iron, Si is the highest impurity level in electrolytic commercial aluminum (0.01 to 0.15%). In wrought alloys, silicon is used with magnesium at levels up to 1.5% to produce Mg2Si in the 6xxx series of heat-treatable alloys.

Titanium. Titanium is added to aluminum primarily as a grain refiner. The grain refining effect of titanium is enhanced if boron is present in the melt or if it is added as a master alloy containing boron largely combined as TiB2. Titanium is a common addition to aluminum weld filler wire as it refines the weld structure and helps to prevent weld cracking.

Vanadium. There is usually 10 to 200 ppm V in commercial-grade aluminum, and because it lowers conductivity, it generally is precipitated from electrical conductor alloys with boron.

Zinc. The aluminum-zinc alloys (7xxx) have been known for many years, but hot cracking of the casting alloys and the susceptibility to stress-corrosion cracking of the wrought alloys curtailed their use. Aluminum-zinc alloys containing other elements offer the highest combination of tensile properties in wrought aluminum alloys. The addition of zinc to aluminum (in conjunction with some other elements, primarily magnesium and/or copper) produces heat-treatable aluminum alloys of the highest strength. The zinc substantially increases strength and permits precipitation hardening. Some of these alloys can be susceptible to stress corrosion cracking and for this reason are not usually fusion welded. Other alloys within this series are often fusion welded with excellent results. Some of the common applications of the 7xxx series alloys are aerospace, armored vehicles, baseball bats and bicycle frames.

Zinc-Magnesium. The addition of magnesium to the aluminum-zinc alloys develops the strength potential of this alloy system, especially in the range of 3 to 7,5% Zn. Magnesium and zinc form MgZn2, which produces a far greater response to heat treatment than occurs in the binary aluminum-zinc system. The strength of the wrought aluminum-zinc alloys also is substantially improved by the addition of magnesium. Increasing the MgZn2, concentration from 0.5 to 12% in cold-water quenched 1.6 mm sheet continuously increases the tensile and yield strengths. The addition of magnesium in excess (100 and 200%) of that required to form MgZn2 further increases tensile strength.

Zinc-Magnesium-Copper. The addition of copper to the aluminum-zinc-magnesium system, together with small but important amounts of chromium and manganese, results in the highest-strength aluminum-base alloys commercially available. In this alloy system, zinc and magnesium control the aging process. The effect of copper is to increase the aging rate by increasing the degree of supersaturation and perhaps through nucleation of the CuMgAl2 phase. Copper also increases quench sensitivity upon heat treatment. In general, copper reduces the resistance to general corrosion of aluminum-zinc-magnesium alloys, but increases the resistance to stress corrosion. The minor alloy additions, such as chromium and zirconium, have a marked effect on mechanical properties and corrosion resistance.

Zirconium additions in the range 0.1 to 0.3% are used to form a fine intermetallic precipitate that inhibits recovery and recrystallization. An increasing number of alloys, particularly in the aluminum-zinc-magnesium family, use zirconium additions to increase the recrystallization temperature and to control the grain structure in wrought products.

Specifications and types of Aluminium alloys

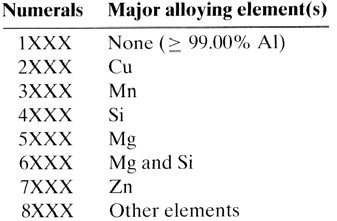

In aluminum specifications, a four-digit index system is used for the designation of cast and wrought aluminum alloys.

These two classes of aluminum alloys can be further subdivided into families of alloys based on chemical composition and on temper designation.

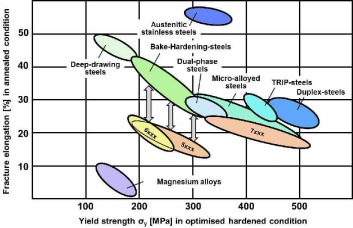

Pure aluminum is mechancially very soft and hence typcially alloyed with many other elements to synthesize a range of materials with a vast variety of physical and mechanical properties.

The alloying elements are used as the nomenclature basis to group aluminum alloys into two types of categories: non-heat-treatable and heat-treatable aluminum alloys.

Most aluminum specifications currently in use designate aluminum alloys in the following way:

First digit – principal alloying constituent(s),

Second digit – variations of initial alloy,

Third and fourth digits – individual alloy variations (number has no significance but is unique).

Wrought Aluminum Specifications. The wrought alloy group is shown as: 1xxx-pure Al (99.00% or greater); 2xxx-Al-Cu alloys; 3xxx-Al-Mn alloys; 4xxx-Al-Si alloys; 5xxx-Al-Mg alloys;

6xxx-Al-Mg-Si alloys.

Cast Aluminum Specifications. The designation system and specifications for cast aluminum alloys are similar in some respects to that of wrought alloys. The cast alloy designation system also has four digits and the first digit specifies the major alloying constituent(s). However, a decimal point is used between the third and fourth digits to make clear that these are designations used to identify alloys in the form of castings (0) or foundry ingot (1,2).

A letter before the numerical designation indicates a modification of the original alloy or an impurity limit. These serial letters are assigned in alphabetical sequence starting with A, but omitting I,O,Q and X, with X being reserved for experimental alloys.

The cast alloy group is shown as: 1xx.x-Pure Al (99.00% or greater), 2xx.x Al-Cu alloys; 3xx.x Al-Si + Cu and/or Mg; 4xx.x Al-Si; 5xx.x Al-Mg; 7xx.x – Al-Zn; 8xx.x- Al-Sn; 9xx.x-Al+Other elements and 6xx.x unused series.

Aluminum Alloy Temper-Designation System. Tempering treatments are essential for aluminum specifications due to their crucial influence on the material properties. The temper designation system is based on the sequences of mechanical or thermal treatments, or both, used to produce the various temper treatments. The temper designation is always presented immediately following the alloy designation with a hyphen between the designation and the temper (e.g.2014-T6, 3003-H14, 1350-H19 (extra hard) etc.). The first character in the temper designation is a capital letter indicating the general class of treatment such as: F-as fabricated; O-annealed; H-strain hardened; W-solution heat treated and T-thermally treated to produce stable tempers other than F,O, or H. Note that the temper designations differ between non heat-treatable alloys and heat-treatable alloys and their meanings are given below.

Non Heat-Treatable Aluminum Alloys. The letter "H" is always followed by 2 or 3 digits. The first digit indicates the particular method used to obtain the temper as follows: H1-means strain hardened only, H2-means strain hardened, then partially annealed and H3-means strain hardened, then stabilized. The temper is indicated by the second digit as follows: 2-1/4 hard; 4-1/2 hard; 6-3/4 hard; 8-full hard and 9-extra hard which means that added digits indicate modification of standard practice. The non heat-treatable alloys are mainly found in the 1xxx, 3xxx, 4xxx, and 5xxx alloys series depending upon their major alloying elements.

Heat-Treatable Aluminum Alloys (e.g. F, O or T): The letter "T" is always followed by one or more digits. These digits indicate the method used to produce the stable tempers, as follows: T3-Solution heat treated and then cold worked, T4-Solution heat treated and then naturally aged, T5-Artificially aged only, T6-Solution heat treated and then artificially aged etc. The heat-treatable alloys are found primarily in the 2xxx, 6xxx and 7xxx alloys series.

In short one also could express hardness as:

H_1 1/8 hard

H_2 1/4 hard

H_3 3/8 hard

H_4 1/2 hard

H_5 5/8 hard

H_6 3/4 hard

H_7 7/8 hard

H_8 Full hard

Heat Treatable Aluminium Alloy Temper Designations

|

Designation |

Description |

Application |

|

O |

Annealed, Recrystalized |

Lowest Strength, High ductility |

|

F |

As Fabricated |

Fabrication with no special control over thermal or strain hardening |

|

W |

Solution Heat Treatment |

Unstable temper application with subsequent period of natural age |

|

T1 |

|

Cooled and naturally aged, i.e. Cooled after being shaped to its final dimensions during a process involving a lot of heat (such as extrusion), then naturally aged to a stable condition.

|

|

T2 |

|

Cooled, cold worked & Naturally aged, i.e. cooled after being shaped to its final dimensions during a process involving a lot of

heat |

|

T3 |

|

Solution heat treated, cold worked & naturally aged. |

|

T4 |

|

Solution heat treated & naturally aged |

|

T5 |

|

Cooled and artificially aged, i.e. more specific, cooled after being shaped to its final dimensions during a process involving a lot of heat |

|

T6 |

|

Solution heat treated and Stabilized, i.e. solution heat treated and artificially aged to a stable condition. T6 is T4 that has been artificially aged. |

|

T7 |

|

Solution heat treated, stabilized to provide special property, i.e. solution heat treated and naturally aged past the point of a stable condition. This process provides control of some special characteristics. |

|

T8 |

|

Solution heat treated, cold worked, artificially aged |

|

T9 |

|

Solution heat treated, artificially aged, then cold worked |

|

T10 |

|

Cooled, cold worked, then artificially aged, i.e. cooled after being shaped to its final dimensions during a process involving a lot of

heat |

Wrought Aluminium alloys (85%)

Non-heat-treatable Al alloys

High-purity Al alloys (1xxx series)

Al-Mn and Al-Mn-Mg alloys (3xxx series)

Al-Mg alloys (5xxxx series)

Heat-treatable alloys (respond to strengthening by heat treatment)

Al-Cu alloys (2xxxx series)

Al-Cu-Mg alloys (2xxxx series)

Al-Mg-Si alloys (6xxxx series)

Al-Zn-Mg and Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys (7xxxx series)

Cast alloys

Al-Si alloys

Al-Cu alloys

Al-Mg alloys

Al-Zn-Mg alloys

Details on commercially used Aluminium alloy grades

Aluminum Grades Series 1xxx

These types of aluminum (1050, 1060, 1100, 1145, 1200, 1230, 1350 etc.) are characterized by excellent corrosion resistance, high thermal and electrical conductivities, low mechanical properties, and excellent workability. Moderate increases in strength may be obtained by strain hardening. Iron and silicon are the major impurities.

Aluminum Grades Series 2xxx

The aluminum 2xxx alloy series (2011, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2124, 2219, 2319, 201.0; 203.0; 206.0; 224.0; 242.0 etc.) require solution heat treatment to obtain optimum properties; in the solution heat-treated condition, mechanical properties are similar to, and sometimes exceed, those of low-carbon steel. In some instances, precipitation heat treatment (aging) is employed to further increase mechanical properties. This treatment increases yield strength, with attendant loss in elongation; its effect on tensile strength is not as great.

The aluminum alloys in the 2xxx series do not have as good corrosion resistance as most other aluminum alloys, and under certain conditions they may be subject to intergranular corrosion. Aluminum grades in the 2xxx series are good for parts requiring good strength at temperatures up to 150°C (300°F). Except for the grade 2219, these aluminum alloys have limited weldability, but some alloys in this series have superior machinability. Aluminum grade 2024 is the most popular alloy and is commonly used in aircraft construction.

Aluminum Grades Series 3xxx

These types of alloys (3003, 3004, 3105, 383.0; 385.0; A360; 390.0) generally are non-heat treatable but have about 20% more strength than 1xxx series aluminum alloys. Because only a limited percentage of manganese (up to about 1.5%) can be effectively added to aluminum, manganese is used as a major element in only a few alloys.

Aluminum Grades Series 4xxx

The major alloying element in 4xxx series alloys (4032, 4043, 4145, 4643 etc.) is silicon, which can be added in sufficient quantities (up to 12%) to cause substantial lowering of the melting range. For this reason, aluminum-silicon alloys are used in welding wire and as brazing alloys for joining aluminum, where a lower melting range than that of the base metal is required. The aluminum alloys containing appreciable amounts of silicon become dark gray to charcoal when anodic oxide finishes are applied and hence are in demand for architectural applications.

Aluminum Grades Series 5xxx

The major alloying element is magnesium; when it is used as a major alloying element or with manganese, the result is a moderate-to-high-strength work-hardenable alloy. Magnesium is considerably more effective than manganese as a hardener – about 0.8% Mg being equal to 1.25% Mn – and it can be added in considerably higher quantities. Aluminum alloys in this series (5005, 5052, 5083, 5086, etc.) possess good welding characteristics and relatively good resistance to corrosion in marine atmospheres. However, limitations should be placed on the amount of cold work and the operating temperatures (150°F) permissible for the higher-magnesium aluminum alloys to avoid susceptibility to stress-corrosion cracking.

Aluminum Grades Series 6xxx

Aluminum alloys in the 6xxx series (6061, 6063) contain silicon and magnesium approximately in the proportions required for formation of magnesium silicide (Mg2Si), thus making them heat treatable. Although not as strong as most 2xxx and 7xxx alloys, 6xxx series aluminum alloys have good formability, weldability, machinability, and relatively good corrosion resistance, with medium strength. Aluminum grades in this heat-treatable group may be formed in the T4 temper (solution heat treated but not precipitation heat treated) and strengthened after forming to full T6 properties by precipitation heat treatment.

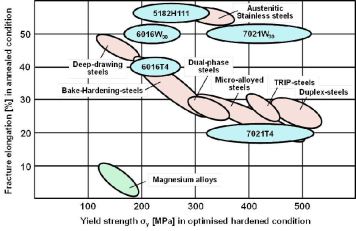

Aluminum Grades Series 7xxx

Zinc, in amounts of 1 to 8% is the major alloying element in 7xxx series aluminum alloys (7075, 7050, 7049, 710.0; 711.0 etc.), and when coupled with a smaller percentage of magnesium results in heat-treatable alloys of moderate to very high strength. Usually other elements, such as copper and chromium, are also added in small quantities. 7xxx series alloys are used in airframe structures, mobile equipment, and other highly stressed parts. Higher strength 7xxx aluminum alloys exhibit reduced resistance to stress corrosion cracking and are often utilized in a slightly overaged temper to provide better combinations of strength, corrosion resistance, and fracture toughness.

Aluminum Grades Series 8xxx

The 8xxx series (8006; 8111; 8079; 850.0; 851.0; 852.0) is reserved for alloying elements other than those used for series 2xxx to 7xxx. Iron and nickel are used to increase strength without significant loss in electrical conductivity, and so are useful in such conductor alloys as 8017. Aluminum-lithium alloy 8090, which has exceptionally high strength and stiffness, was developed for aerospace applications. Aluminum alloys in the 8000 series correspond to Unified Numbering System A98XXX etc.

Mechanical properties of some selected commercial aluminium alloys

|

Alloy |

Temper |

Proof Stress 0.2% (MPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Shear Strength (MPa) |

Elongation A5 (%) |

Hardness Vickers (HV) |

|

AA1050A |

H12 H14 H16 H18 0 |

85 105 120 140 35 |

100 115 130 150 80 |

60 70 80 85 50 |

12 10 7 6 42 |

30 36 - 44 20 |

|

AA2011 |

T3 T6 |

290 300 |

365 395 |

220 235 |

15 12 |

100 115 |

|

AA3103 |

H14 0 |

140 45 |

155 105 |

90 70 |

9 29 |

46 29 |

|

AA4015 |

0 H12 H14 H16 H18 |

45 110 135 155 180 |

110-150 135-175 160-200 185-225 210-250 |

- - - - - |

20 4 3 2 2 |

30-40 45-55 - - - |

|

AA5083 |

H32 0/H111 |

240 145 |

330 300 |

185 175 |

17 23 |

95 75 |

|

AA5251 |

H22 H24 H26 0 |

165 190 215 80 |

210 230 255 180 |

125 135 145 115 |

14 13 9 26 |

65 70 75 46 |

|

AA5754 |

H22 H24 H26 0 |

185 215 245 100 |

245 270 290 215 |

150 160 170 140 |

15 14 10 25 |

75 80 85 55 |

|

AA6063 |

0 T4 T6 |

50 90 210 |

100 160 245 |

70 11 150 |

27 21 14 |

85 50 80 |

|

AA6082 |

0 T4 T6 |

60 170 310 |

130 260 340 |

85 170 210 |

27 19 11 |

35 75 100 |

|

AA6262 |

T6 T9 |

240 330 |

290 360 |

- - |

8 3 |

- - |

|

AA7075 |

0 T6 |

105-145 435-505 |

225-275 510-570 |

150 350 |

9 5 |

65 160 |

What is the Influence of Copper on Aging in Aluminium-Magnesium Alloys ?

Acta Materialia 161 (2018) 12

Acta Mater 2018 Cluster hardening Al-3Mg[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.1 MB]

The aging response of two Al-3Mg alloys with Cu addition <1 wt% has been tracked under simulated automotive paint bake conditions (20 min, 160 and 200 °C) to quantify the processes controlling hardening. The decomposition of the solid solution, observed by atom probe tomography, has been interpreted using a novel pair correlation function approach and incorporated into a model for prediction of precipitation hardening. It is shown that the hardening is controlled by clusters/Guinier-Preston-Bagaryatsky (GPB) zones similarly to what has been previously observed in much higher Cu containing 2XXX-series alloys. Interestingly, it is shown that very small additions of Cu (< 0.1 at%) can be used to catalyze a high number density of strengthening particles owing to the high enrichment in Mg compared to particles found in more conventional high Cu/low Mg alloys. This allows hardening during the first hour of aging that is as high as that obtainable in these high Cu alloys.

What is the influence of equilibrium grain boundary segregation on precipitation in a Al-Zn- Mg-Cu alloy?

Acta Materialia 156 (2018) 318

Acta Mater 2018 Segregation assisted gra[...]

PDF-Dokument [4.6 MB]

Understanding the composition evolution of grain boundaries and grain boundary precipitation at nearatomic scale in aluminum alloys is crucial to tailor mechanical properties

and to increase resistance to corrosion and stress corrosion cracking. Here, we elucidate the sequence of precipitation on grain

boundaries in comparison to the bulk in a model Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. We investigate the material from the solution heat treated state (475 °C), through the very early stages of

aging to the peak aged state at 120 °C and further into the overaged regime at 180 °C. The process starts with solute enrichment on grain

boundaries due to equilibrium segregation accompanied by solute depletion in their vicinity, the formation of Guiniere-Preston (GP) zones in the solute-enriched grain boundary

regions, and GP zones growth and transformation. The equilibrium segregation of solutes to grain boundaries during aging accelerates this sequence compared to the bulk. Analysis of the ~10

nm wide precipitate-free zones (PFZs) adjacent to the solute-enriched grain boundaries shows that the depletion zones are determined by (i) interface equilibrium segregation; (ii) formation

and coarsening of the grain boundary precipitates and (iii) the diffusion range of solutes in the matrix. In addition, we quantify the difference in kinetics

between grain boundary and bulk precipitation. The precipitation kinetics, as observed in terms of volume fraction, average radius, and number density, is almost identical next to the depletion

zone in the bulk and far inside the bulk grain remote from any grain boundary influence. This observation shows that

the region influenced by the grain boundaries does not extend beyond the PFZs.