Nanolaninate Steels: Pealite and Martensite-Austenite Reversion Steels

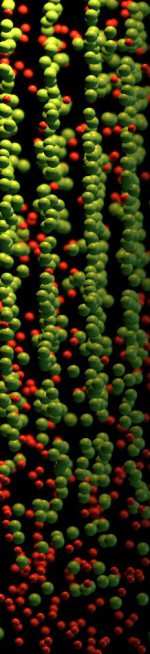

Many different types of steels consist of micro- or nanoscale laminate microstructures.

A typical example are pearlitic steels which consist of a lamellar structure of alternating iron and iron carbide (cementite) layers.

Cementite is an iron carbide with Fe3C stoichiometry and orthorhombic crystal structure. The eutectoid concentration of the alloy lies at the eutectoid temperature-composition intersection where the

austenite phase transforms directly into a layered ferrite-cementite solid. This is referred to as a pearlitic reaction.

Upon heavy deformation this laminate microstructure undergoes substantial refinement down to the nanometre scale.

Upon further large straining the carbide phase dissolves via mechanical alloying, rendering the initially two-phase pearlite structure into a carbon-supersaturated iron phase.

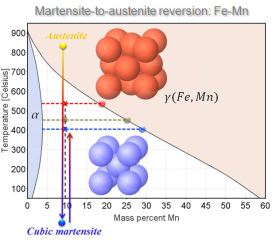

Another case where laminate steels have been designed are martensite reversion steels. In these materials the alloy is first rendered austenitic and then quenched into the martensitic state. After

that the so quenched material is subjected to a martensite-to-austenite reversion heat treatment.

This works by annealing the martensite into a temperature regime where local austenite formation can occur, either at segregation decorated defects for instance at grain (lath)

boundaries.

Since many types of martensite steels can contain very fine lath grain boundary structures such a reversion heat treatment can be used to create very fine damask-type nanlaminate microstructures

leading to steels with superior mechanical properties for instance when subjected to fatigue loading scenarios.

Below are some more specific examples for such nano-laminate steels.

Phase nucleation through confined spinodal fluctuations at crystal defects evidenced in Fe-Mn alloys

Analysis and design of materials and fluids requires understanding of the fundamental relationships between structure, composition, and properties. Dislocations and grain boundaries

influence microstructure evolution through the enhancement of diffusion and by facilitating heterogeneous nucleation, where atoms must overcome a potential barrier to enable the early stage

of formation of a phase. Adsorption and spinodal decomposition are known precursor states to nucleation and phase transition; however, nucleation remains the less well-understood step in

the complete thermodynamic sequence that shapes a

microstructure. Here, we report near-atomic-scale observations of a phase transition mechanism that consists in solute adsorption to crystalline defects followed by linear and planar

spinodal fluctuations in an Fe-Mn model alloy. These fluctuations provide a pathway for austenite nucleation due to the higher driving force for phase transition in the solute-rich regions.

Our observations are supported by thermodynamic calculations, which predict the possibility of spinodal decomposition due to magnetic ordering.

Silva_et_al-2018-Nature_Communications S[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.7 MB]

Nanolaminate Steels based on Pearlite

Pearlitic steel can exhibit tensile strengths above 7 GPa after severe plastic deformation, where the deformation promotes a refinement of the lamellar structure and cementite decomposition.

With is they are the strongest formable bulk metallic alloys.

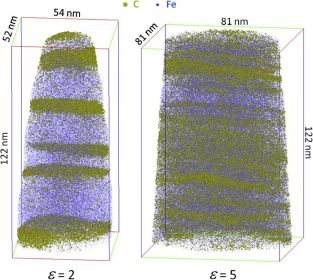

A clear correlation between deformation and cementite decomposition in pearlite is still absent. In our recent works, a local electrode atom probe was used to characterize the

microstructural evolution of pearlitic steel, cold-drawn with progressive strains up to 5.4. Transmission electron microscopy was also employed to perform complementary analyses of the

microstructure. Both methods yielded consistent results. The overall carbon content in the detected

volumes as well as the carbon concentrations in ferrite and cementite were measured by atom probe. In addition, the thickness of the cementite filaments was determined. In ferrite, we found a

correlation of carbon concentration with the strain, and in cementite, we found a correlation of carbon concentration with the lamella thickness. Direct evidence for the formation of

cell/subgrain boundaries in ferrite and segregation of carbon atoms at these defects was found. Based on these findings, the mechanisms of cementite decomposition

are discussed in terms of carbon–dislocation interaction.

Scientific Reports | 6:33228 | DOI: 10.1038/srep33228

Ultrastrong damage tolerant Scientific R[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.7 MB]

Acta Materialia 59 (2011) 3965

Acta Materialia 59 (2011) 3965 pearlite [...]

PDF-Dokument [1.0 MB]

Acta Materialia 60 (2012) 4005

Acta Materialia 60 (2012) 4005–4016 heat[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.7 MB]

Acta Materialia 84 (2015) 110

Acta Materialia 84 (2015) 110-123 atom p[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.4 MB]

Djaziri et al. Advanced Materials, Vol 28, IS 35, pages 1521-4095

Djaziri_et_al-2016-Advanced_Materials.pd[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.2 MB]

PRL 113, 106104 (2014)

Li and Raabe Phys Rev Lett vol 113 page [...]

PDF-Dokument [1.6 MB]

PRL 112, 126103 (2014)

Phys Rev Lett. 2014 grain boundary segre[...]

PDF-Dokument [842.8 KB]

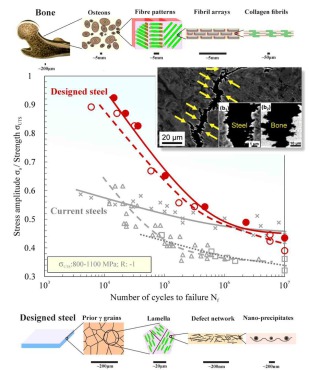

Martensite-to-Austenite Reversion Steels

Steels containing reverted nanoscale austenite laminate regions or reverted austenite islands or films dispersed in a martensitic matrix show excellent strength, ductility and toughness. They can be synthesized by a simple reversion heat treatment of as-quenched martensite to bring the material locally into the two-phase austenite-martensite region.

Koyama et al., Science 355, 1055–1057 (2017)

Koyama Bone-like Steels Science 355 (201[...]

PDF-Dokument [745.8 KB]

Acta Materialia 85 (2015) 216

Acta Materialia 85 (2015) 216 Nanolamina[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.3 MB]

Acta Materialia 61 (2013) 6132

Acta Materialia 61 (2013) 6132–6152 Nano[...]

PDF-Dokument [2.3 MB]

Science 349, 1080 (2015); M. Kuzmina et al.

Linear Complexions Science vol 349 (2015[...]

PDF-Dokument [1.5 MB]

Scripta Materialia 60 (2009) 1141

Raabe Scripta Materialia 60 (2009) 1141 [...]

PDF-Dokument [342.1 KB]